When Fernando Alonso described Robert Kubica as "a legend of our sport" after his old Formula 1 rival won the Le Mans 24 Hours, he wasn't exaggerating.

The level of respect for Kubica in the grand prix paddock remains high among those who raced against or worked with the Pole, who is the great 'what if?' story of the 21st century.

Did what happened on that fateful Sunday during the Ronde di Andorra rally in February 2011 cost F1 a world champion? Very possibly.

There's no chance it would have happened in 2011 in a Renault with forward-facing exhausts that produced good initial performances but didn't respond to upgrades, but Kubica likely would have grabbed some good results early on. However, he was destined to move to Ferrari to partner Fernando Alonso the following year.

Kubica showed enough during his four full seasons in F1 before the crash that changed his life to prove that he would certainly have won races with Ferrari. As for the world championship, there's no doubt he was capable of it, but given Ferrari hasn't won a title since 2008 it's hardly a forgone conclusion. If he hadn't, where the next step might have taken him is impossible to say.

But more important than the might-have-beens is what Kubica did achieve in F1. And by this, we're talking about original version rather than the one who returned in 2019 with Williams, and for two outings for Sauber in 2021, while driving "70% left-handed".

What he went through and then overcame in returning was, in itself, an astonishing achievement that arguably eclipses that of winning a world championship despite yielding just a single point. But it wasn't the crowning glory he craved, and his recent Le Mans 24 Hours win at least partly makes up for that.

Kubica forced his way into a race seat with BMW Sauber at Jacques Villeneuve's expense through his pulverising pace in testing and Friday outings in 2006. In a car with a touch of understeer, he could carry phenomenal entry speed on the grippy Michelins and get the car to respond well enough to give the required rotation. It was similar to what Alonso could do, at times perhaps even more impressive.

The result was seventh place on-the-road on debut in Hungary (a result he was stripped of for the car being underweight) then a first podium at Monza on his third start.

The following year was a more difficult one, with tyre competition eliminated by Michelin's departure and the resulting switch to Bridgestone rubber, with a more oversteery balance, making it difficult for Kubica to do his best work.

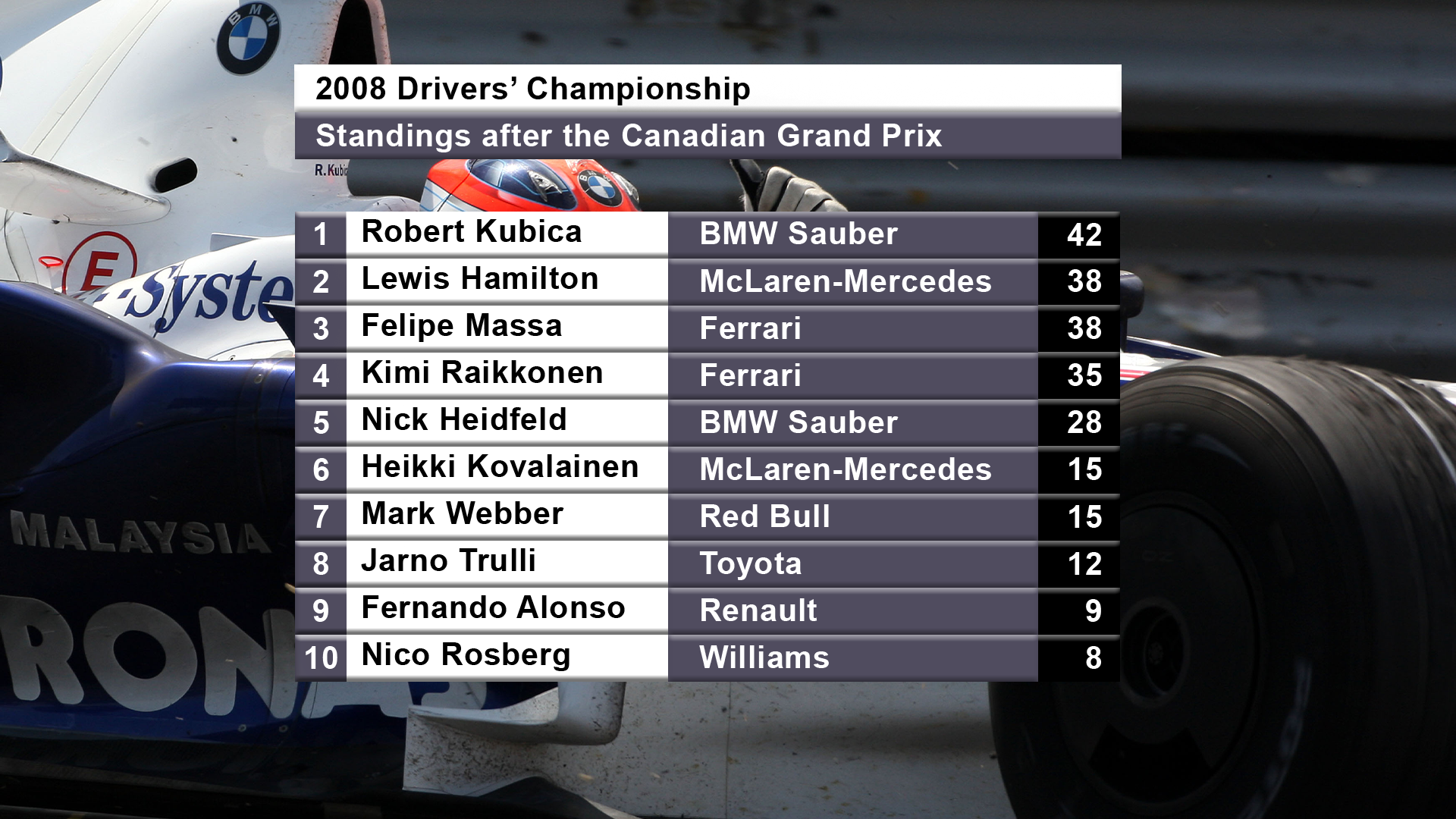

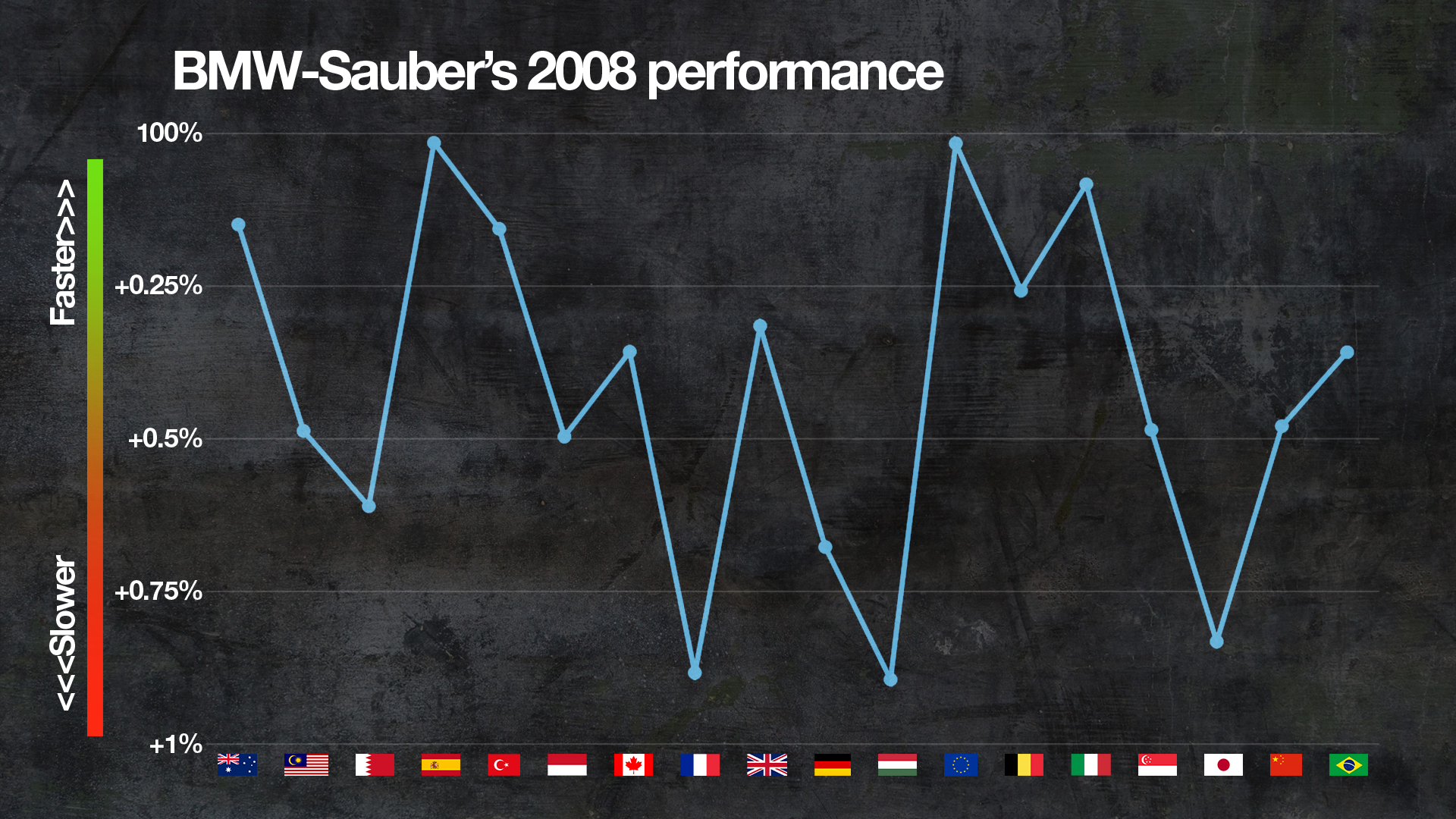

So the 2007 season was not so impressive, but he returned to form in 2008 with BMW Sauber and tyres that tended more to understeer and comprehensively outperformed team-mate Nick Heidfeld. Some, including myself and my then-Autosport colleague Mark Hughes, rated him as the best driver of the season.

That campaign is best remembered for Kubica's frustration. He believes BMW felt it was job done and as the season progressed decided to focus more on improving Heidfeld's performances, the consequence of hitting the corporate schedule by winning - through Kubica - in Canada.

Kubica argues there were upgrades that could have been brought to the car that were not, and to this day he angrily regrets BMW preventing him from going for the championship by not pushing on as it should have done with developing the car.

The Montreal win was Kubica's crowning glory in F1, coming a year after his massive accident there, but was not his best performance of the season. That honour perhaps goes to his second place after leading early on at Fuji in a car that was no longer as competitive as it previously was.

BMW expected 2009 to be its title-winning year, but it proved disastrous. The introduction of KERS, something BMW stood in the way of F1 postponing, was a big part of the problem.

It meant the car was overweight with packaging compromised, primarily because of the placement of the air-cooled batteries, with head of engineering Willy Rampf admitting "we underestimated the complications and impact they had on the car". KERS was dropped early in the season, but many of the compromises remained.

The wider front wings also created aero problems and there was also no double diffuser, an innovation team principal Mario Theissen blames for BMW's 2009 failure.

BMW pulling the plug forced a move to another team, but despite interest from Williams Kubica opted for Renault.

There, the team responded well to his demanding personality. While the Renault R30 of 2010 was a tidy car, Kubica played a big role in improving it by pushing for power steering and braking changes early on to ensure he got the stability, the feel, and the level of responsiveness he needed for his trademark corner entry speed.

The result was an outstanding season. Monaco, where he qualified second and finished third, was particularly memorable even though Kubica himself said "I was massively helped by the car there, it was very friendly, very easy to predict".

He characterised the R30 as "not the fastest, but probably the easiest" car he experienced in F1 that gave him the freedom to drive as he wanted. At Suzuka, he qualified third with floor damage that cost rear downforce, which stands as one of the most impressive Saturday performances of recent memory.

Who knows what Kubica might have made of the very competitive 2012 Lotus-Renault, which Kimi Raikkonen took to a win in Abu Dhabi, had he still been there? Chances are, he'd have been in Ferrari red by then and struggling with a troubled car, but it seems inconceivable that he wouldn't have found his way into a car that could have won the world championship at some point.

That's why he's a driver who still commands enormous respect in F1. Alonso in particular knows how good Kubica was and the intra-Ferrari battle between the pair of them would have been one for the ages.