With every team now focusing on development of the new 2026 cars - which performance-wise won't have very many carry-over parts - we don't expect to see much in the way of major upgrades when the Formula 1 season restarts following the August break. But that doesn't mean the competitive order can't change.

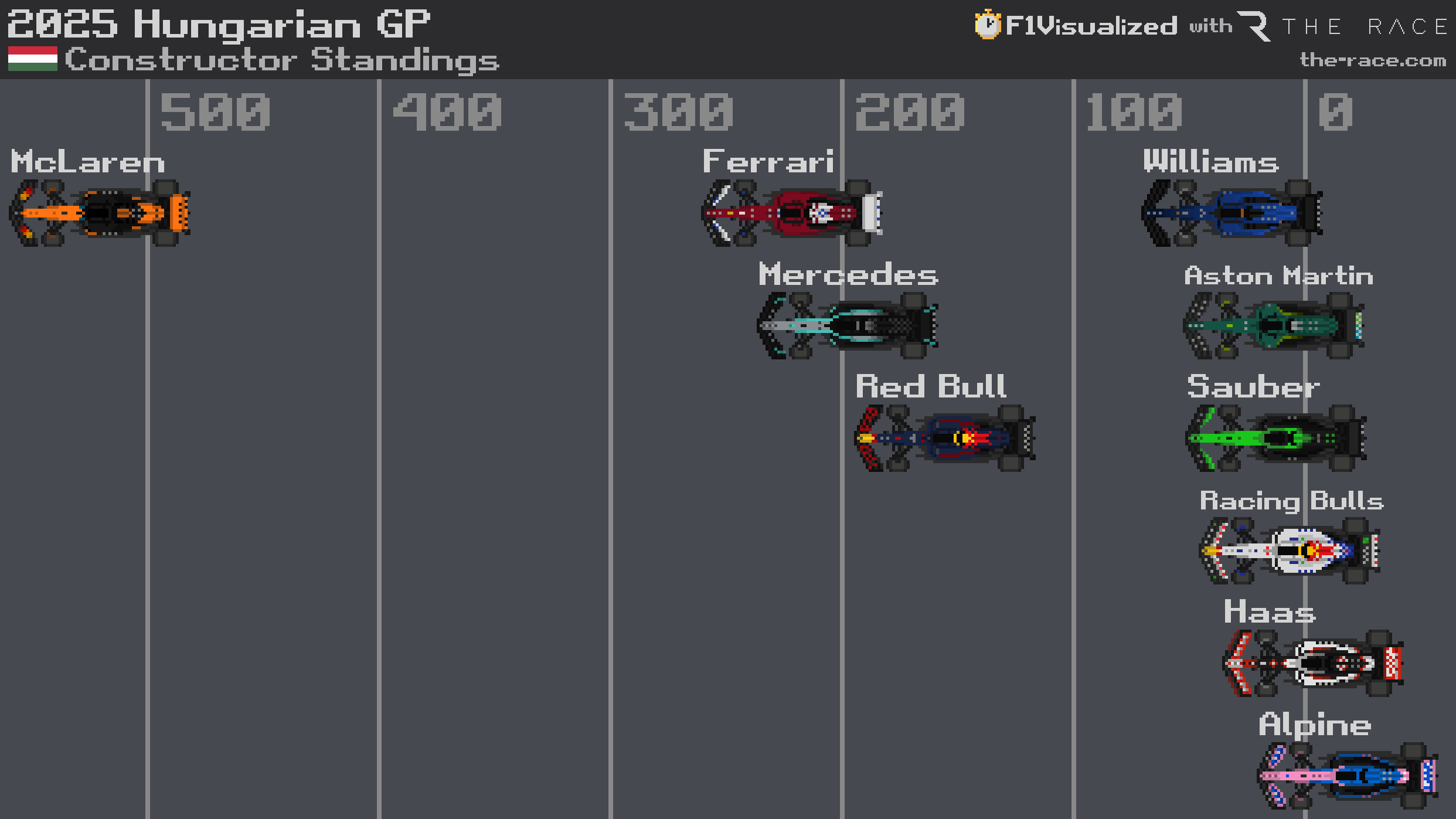

Other than the pride of winning more individual races, McLaren doesn't have too much to worry about, but from there on down there are still a lot of points to fight for.

Most teams say they have no more major developments to come. Although we will likely see some small bits and pieces appear to optimise what they already have, it's the teams that have a championship position to fight for or major problems to troubleshoot who will still be tempted to split their resources.

Even with some minor optimisation upgrades to come, the development war will shift to become more a battle to get the best out of what you already have. I can assure you that there is more performance available for each team and in effect each driver given that they will be driving and engineering more or less the same car for the next 10 races.

One of the problems with constantly adding upgrades that should make the car faster is that its characteristics are always changing. This means that you have to keep relearning the car and subtly tweak your set-up approach, but if your car remains unchanged then you can concentrate on making the most out of it.

There are limits to what's possible, but it's not as obvious as you might think when it comes to whether it's an advantage to upgrade the car to raise the theoretical performance or simply do a bit better with what you've got.

Over a normal race weekend, running time is limited - even more so over a sprint weekend. This means set-up changes have to take that into account and anything that would take more than, let's say, 15 minutes would need to be put on the backburner and changed between sessions. The problem with that is that the track grip level or the wind direction will have changed, effectively making the performance comparison result dubious.

Having more or less the same car specification from one weekend to another means that you can devote more time to those potentially whacky set-up changes. You can experiment with, let's say, a softer set-up and run the car just that little bit higher to see how it affects tyre degradation. Or, you could experiment with side-spring stiffness compared to central (third spring) stiffness.

The set-up options are endless, but when you have new developments on the car every weekend your time is spent trying to optimise them. Achieving that can be worth a significant amount of laptime.

However, if you experiment with a set-up that, let's say, makes the car in simulation a tenth of a second slower, but gives the drivers confidence and predictability, then that could be worth two or three tenths in time. If you never have the chance to try set-up directions that shouldn't work, you won't necessarily find the true sweet spot of the car.

It's always the aerodynamic characteristics that catch you out. In the past, not having new components on the car allowed us to test less-peaky downforce components including front wings, front wing endplates, underfloor splitters or bargeboard configurations (when they were allowed). Basically, anything that was working near the track surface could very easily cause sensitivity problems and it's not until you run them at the circuit that the problems show up.

Having time to go through these older spec and, in effect, less potentially performant components and focus more on reducing sensitivity and therefore driver errors can be very worthwhile.

I can remember fitting new parts and the driver being initially in raptures about them, but they didn't really notice that suddenly they were struggling to get more than one clean lap out of three from the car. By the end of the session, when push came to shove and you were pushing for a laptime from only one lap, those mistakes would raise their ugly heads and we would suffer from not getting the potential out of the car.

The end to the 2025 season is an interesting one because normally there would be some teams introducing fairly major upgrades late in the year, which could upset the running order. The major regulation changes, means as I said above that there is very little carryover and all the teams will be focused on getting that new package finalised in preparation for the earlier-than-normal winter shakedown tests in late January.

Competitiveness is relative: it's all about being faster than your closest opposition. In reality, you are in the hands of the others and how much progress they do or don't make. Those who might be concerned about the lack of new parts, though, aren't necessarily going to be at a disadvantage this year.

With the field so compact in terms of performance, small swings either way can make a big difference. On average, across the first 14 events, the gap from front to back using our 'supertimes' metric - based on each team's fastest single lap of a weekend expressed as a percentage of the outright fastest - is just 1.6%. That's around 1.3s around an 80-second lap, so if you can gain a tenth or two then that can make the difference between challenging for Q3 and falling in Q1. And often if you find speed in qualifying, it will translate to race pace - especially if you make that gain through driver confidence as often than can mean tyre management is easier.

We should look at these 10 races as an individual part of the championship. Getting the best out of what you have got is more down to the race engineering group and the back-at-base simulation and analysis group as opposed to the design group that creates the car. Although everyone works for the same team, it is this split that sometimes holds teams back. Blame culture is never a good thing and the team that avoids that usually prospers. At the moment McLaren seems to do that best. As for the others, some could still improve in this area.

When the champagne (or rather rose water) corks finally pop in Abu Dhabi, we will know who really had most performance left untapped.

Will Alpine be able to drag itself up from the bottom of the pile? Can Aston Martin maintain its Hungary form? Will we actually see the long awaited 'incident' between the two McLaren drivers?

And what will the driver line-up actually be when the final chequered flag for 2025 falls?