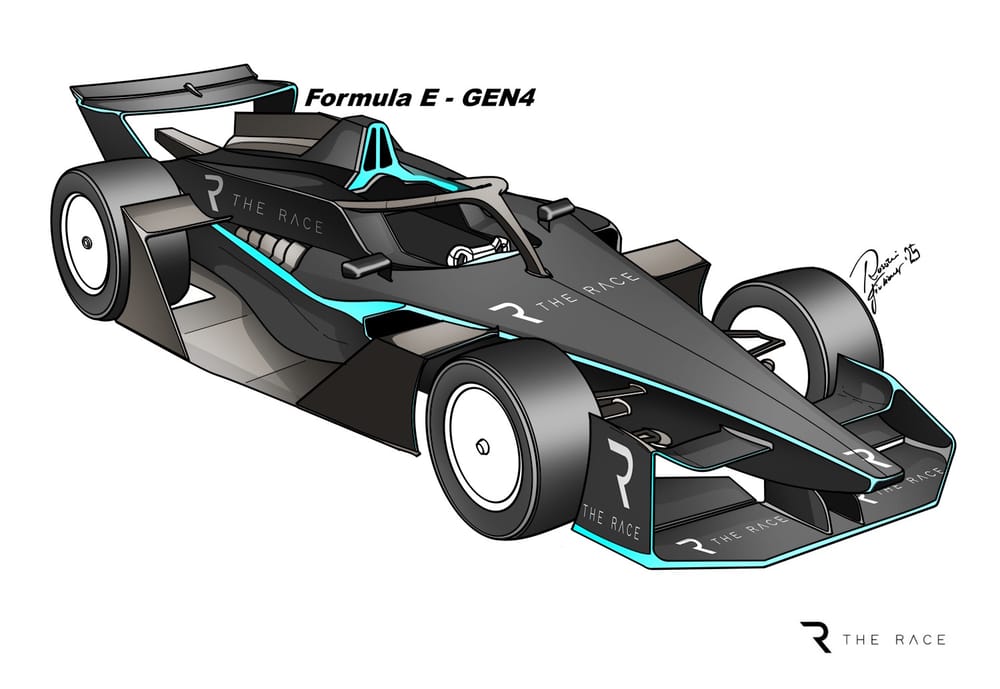

The Race can reveal what the Gen4 Formula E car is set to look like after recently receiving some detailed information about the design plans for what will be the all-electric world championship's quickest and most powerful machine.

Based on information seen and received by The Race, the design shown in our mock-up features several notable changes when compared to the current Gen3 Evo car in use until the end of the 2025-26 season.

The new model, a prototype version of which has been testing over the last three months, is set to be produced and delivered to registered manufacturers this September, with some of them expected to commence testing a month later.

It will run in permanent four-wheel-drive specification as opposed to the current car, where four-wheel drive is only active in the duel phase of qualifying, the race start, and in attack mode.

And it will have a maximum power of 600kW, up from 350kW, while energy recuperation will also be increased from 600kW to 700kW.

From a side profile, the Gen4 car looks like a traditional, powerful single-seater, with a resemblance to a Super Formula or Formula 2 car, but it will still have some carryover Gen3 aesthetic traits. In essence, though, this will be distinctive enough to attract the usual lovers and haters when it comes to its looks, just as its Gen2 and Gen3 predecessors did.

The dimensions of the Gen4 cars include the car being 520mm longer than the Gen3 Evo. It has a wheelbase of 3080mm, compared to the present 2705 mm; and a width of 1800mm versus the Gen3 Evo's 1707mm.

The Race has learned that a collective test for all manufacturers to share basic initial development knowledge of the car is tentatively pencilled in for November after the official and regular pre-season and women's test occurs at the end of October.

The private testing window for manufacturers opens on January 1 2026. Nissan, Jaguar, Porsche, whichever of its brands the Stellantis group choses to enter and Lola are the five manufacturers registered presently, while Penske and Mahindra could become late entries.

Here, the main features of the new package and what it might mean for racing in the Gen4 era, which will kick off in around 16 months' time, are laid out as Formula E gets set to embark on a crucial hike in power and performance that it hopes will boost its popularity and result in genuine viewership uptake.

The heaviest Formula E car yet

The Gen4 car has significantly more power, grip and downforce than its Gen3 predecessor, but it is also longer and wider.

For the Gen3 car, the FIA searched out a latest-spec battery. A pouch cell by Saft was selected given it boasted high energy density but also pushed the boundaries for charge rates, something which would be especially beneficial to achieve the desire to showcase fast-charging capabilities in pitstops - which have finally happened this season.

The cell itself was not intrinsically an issue but the supply of hardware in the pandemic and post-pandemic period from 2020-23 was certainly a challenge with cells (and their raw materials) particularly difficult to secure.

It is also worth mentioning that the FIA's initial tender targets could only be achieved by the use of exotic (pouch) cells. The tender winner therefore entered into a kind of mutual risk share where both sides knew they were completing something innovative and inherently challenging.

What the FIA also did not anticipate is that, by picking an exotic cell, its battery supplier Williams Advanced Engineering (now Fortescue Zero) would have to deal with new-tech reliability issues and latterly supply difficulties.

The other factor that has the most pronounced effect on battery reliability is undoubtedly the significant scope creep with respect to track design and associated duty cycles, which have clearly increased way above the original tender targets, specifically at tracks such as Portland and Misano (used in 2024).

Some believe that Fortescue Zero has done a fine job of finding ways to allow for this duty cycle increase rather than ultimately restricting the series and accruing a big risk in doing so.

Subsequently, for the Gen4 project, the FIA pursued a philosophy of simplification with the battery. Along these lines, the battery tender process selected an overall solution featuring a more traditional cell design.

With a desire to deliver a big step in car performance and therefore a need to have more energy on board to feed higher power rates for the powertrains, an overall larger and heavier battery will feature at the heart of the Gen4 car. Therefore, the Gen4 will weigh in at 1016kg compared to the 859kg of the Gen3 Evo.

Fortescue Zero was naturally disappointed that its tender wasn't chosen for the Gen4 design. It faced a fraught period in the early days of Gen3 to comply with the FIA's spec and wrestle with the supply and early reliability evolutions of the Saft pouch.

There have been reliability issues with the Gen3 units but this season these appear to largely have disappeared, although cell supply frustrations are still something of a challenge.

New supplier Podium Advanced Technologies has some experience in this field having supplied the MotoE grid before. But the tech specialist, whose most notable motorsport project so far was on the Glickenhaus Hypercar that competed in the World Endurance Championship between 2020 and 2022, has to rise to the challenge of scaling up for Formula E supply in Gen4.

Is the move to a more conventional cylindrical battery supply the best option for Gen4? Practically it probably is, but from the point of view of innovation and weight increase (which impacts on freight), the inertia in accidents, and the all-round package, it is probably less so.

Are two aero configurations necessary?

The Gen4 cars will come with two different downforce steps - low and high - via body kits that will be used by teams at specific races. This an FIA-driven move which is already being questioned by manufacturers.

This added kit and the fact that two types of tyre, in essence a cut slick and rain tyres, are to be carried by teams has not only raised the predicament of freight cost and sustainability implications but also whether the added complication and cost is necessary.

One solution will be to use the wet tyres as travelling tyres but there is still no getting away from the fact that in the Gen4 era there is likely to be more travelling weight, something that Formula E Operations has been proud of reducing in recent seasons.

On the performance side, one thing that Formula E cars have always been able to do is to follow closely and maintain ultra-close racing. But might this be jeopardised by the two aero configurations and higher grip direction now?

Increasing car performance, perhaps to around Formula 2 levels, and adding different downforce levels might prove difficult in high energy races in the sense that it could contribute to consuming lots of energy.

This could change how races are structured compared to Gen3, although the sporting make-up of Gen4 racing is largely undecided yet other than the FIA carrying over the 'PitBoost' energy top-up pitstops - although this is not absolutely guaranteed to be a part of the sporting framework yet.

Clearly the FIA wants the cars to be much quicker on laptime but will that come at the cost of Formula E's greatest USP of sensationally close racing? It's a concern that some teams have at the moment.

What Gen4 racing will look like

Performance-wise, the increased downforce will have an implication in terms of requiring teams to have a greater aero understanding than they do at present. That may seem like a very obvious statement but since the advent of Formula E it hasn't actually been a huge requirement in knowledge.

There isn't an adjustable flap on the rear-wing of the Gen3 design. But when there is a more powerful aero characteristic via the elongated underbody in Gen4 it starts to become more important to understand and get right.

The increase in power and possibly a so-called 'lift delta' in saving energy will be a big step for Formula E. In terms of actual sessions and how they are run, clearly there can't be cars with such a big speed delta on track together, so there will likely be a delineation on what power and what aero configuration teams can run and when.

It is difficult to accurately simulate the impact of one car on another with a new design although the FIA does have a bespoke capability for such work. Testing how cars react behind each other is not something that can be tested in real-time - until, that is, a bunch of cars meet on any given track.

Looking back at the start of the Gen3 era, there seemed to be a bit of a misunderstanding early on when one assumption appeared to be that the car had more drag than it actually showed. In fact, the drag was very similar between Gen2 and Gen3 and what really changed was the amount of recovery (in energy) that was gained under braking.

Getting more energy back and then snowballing over a race distance obviously induces pack-racing, as has been seen since Gen3 began in 2023. For Gen4 there will still be a powerful regen tool on the front axle, the front powertrain kit (FPK), but the amount of drag benefit and lift delta isn't yet fully understood.

In Gen3 racing, drivers are able to closely follow the car ahead through a fast corner, up to a braking point, and therefore get more energy back because the following car is at a slightly higher speed of the two.

It's not clear if that will be possible in Gen4 and if there is a big turbulent wake behind, which is likely, then following a car through a high-speed corner might be challenging, especially by the time the car gets to the next braking point, by which time it might actually not be faster and might not get the benefit of recouping energy either.

Generally, the more downforce added, the more turbulent the airflow and the drag that goes with the lift will be. It might spell very heavy pack-racing at some tracks and, not quite as significantly, peloton races at others. This is because the cars just might not be able to follow so closely in the airflow coming off the car ahead.

It may not just affect the balance but also the drag and therefore, even if it slows the following car in the corner, it might be even faster in the next straight, so there's a yin-and-yang for teams to deal with. These possibilities will only be known in the initial testing phase later this year when more than one Gen4 car is on-track at the planned manufacturer test days.

The financial questions

The commercial demands on the teams, which will still of course work to strict financial regulations, has been amplified by more component items being put back into the so-called manufacturers' perimeter in the regulations.

As an example, the chassis loom and DC/DC motor parts were common supply items but are now within the manufacturers' domain. The chassis loom, an integral part of the car, was initially not included to facilitate cheaper and easier chassis changes because the looms would be the same.

Now customer teams might not be able to get a chassis from spares supplier Spark more readily for a quick turnaround in the event of a survival cell change, although The Race understands that this has been discussed at length in various Technical Work Group meetings.

Then there are the active differentials at both ends of the car, which will be a hydraulic design and adds complication and expense. This is commonplace in Formula 1 and the World Rally Championship but the FIA could have done that electronically, which seems to be the most obvious solution for an electric championship.

How teams might master Gen4

One of the likely areas where teams will be able to make a big difference is a new openness for rear differential design.

The front diff too will give opportunity, even if the front powertrain is now spec and supplied by Marelli. That is because teams will now be able to map the FPK forensically.

But it is the rear differential where there could be a real technical battle between manufacturers. Potential experimentation with a small hydraulic actuator pushing on plates is likely to be pursued to activate an advantageous locking mechanism.

The Gen4 cars will of course also be more physical to drive due to the weight and extra speed and grip. But with power steering they should be pretty manageable all-round.

One aspect that can only be controlled so much are accidents. Clearly with more power comes more mass in terms of impacts and that requires a lot of momentum and energy calculation to check the tracks are sufficient in terms of safety.

The FIA has an exceptional safety department and it will go through its analysis thoroughly. The Gen4 car will likely have some implication on track design, even if it means that all of the same tracks are used but with an advisory on key areas where the next generation carry more energy than before, so that extra absorption is utilised in barrier design and placement.

The two tracks where there might have to be at least modification, or indeed a venue change, are likely to be Jarama and London. The former is yet to be raced on but does have limitations, particularly at the quick final corner, where the runoff is extremely limited.

London's ExCeL venue has no real expansion possibilities and as a consequence may be dropped for the 2026-27 season, with a move to Silverstone or Brands Hatch long being mooted.