Mercedes is tipped by many to be back on top in Formula 1 for the start of the new regulations era in 2026. There are good reasons for this, given the team’s illustrious history, the quality of its personnel, top-notch facilities, spectacular success last time the engine regulations were overhauled in 2014, and it being at the centre of an early potential 2026 loophole. However, there are also doubts.

That’s because Mercedes failed to conquer the ground-effect regulations of 2022 to 2025. It will only be by avoiding the mistakes that blighted the past four years, when it was only the fourth-most-successful team in terms of results, that it can live up to its prodigious potential. And everyone in the team knows that, as the difficulties of the past four years leave no room for complacency.

“I’m never confident,” said team principal Toto Wolff. “I’m a glass-half-empty person, so we’ll just do everything we can that is in our power to come out with a car, with a power unit that is competitive enough to fight for a world championship.”

It’s impossible to know the relative competitiveness of the brand-new power units, which are conceived to have a power split of roughly 50-50 between the conventional V6 internal combustion engine and the electric motor. But there are reasons to be optimistic about the Mercedes power unit design even though it won’t be until it runs on track that we can see how it really stacks up.

But even if it’s the market leader propulsion-wise, Mercedes must still prove it can beat its customer teams - Williams, Alpine and, crucially, McLaren. As Wolff said in Abu Dhabi at the end of the 2025 season: "this power unit has won a constructors’ world championship, that means our car wasn’t good enough to beat McLaren". So to recapture the glory days, Mercedes not only requires a strong power unit, but also a cutting-edge chassis.

And while the car regulations have been transformed as part of arguably the biggest rules overhaul in grand prix history, the 2026 Mercedes is the product of much the same tools, process and people that never got it right in the ground-effect era.

There are countless reasons why Mercedes was a consistent frontrunner but never took the step to become a championship threat from 2022-2025, when it finished second in the constructors’ standings twice, but looking at the big picture there are four key mistakes that encapsulated its problems.

Mistake 1 - Making a bad start

Starting a new regulations era well has always been important in F1. If you launch with broadly the right concept you can plough serenely on with improving it, but if you’re on the wrong track, you divert development resources to corrective action while others are only getting quicker. It’s rare for a team to do what McLaren did in this era and turn things around after a bad start.

The cost cap and the aerodynamic testing restrictions introduced in 2021 have made this an even bigger concern. A big team used to be able to use brute-force spending to catch up, now that’s impossible.

“We got off to a wrong start,” said Wolff of Mercedes' problems under the 2022-25 rules. “We tried to solve it problem by problem and while peeling off and sorting these problems, new problems occurred and we were never able to correlate and understand.”

Mercedes launched with the infamous zero-sidepods W13 at the start of the ground-effect rules in 2022. It was certainly innovative, with only Williams having a similar design. Williams ditched that mid-season, but Mercedes persevered.

In simulation, the car produced eye-watering levels of downforce and the rumour-mill had it that Mercedes looked mighty. Unfortunately, when the car ran in the real world it was badly hit by porpoising. That was the beginning of Mercedes not quite mastering the regulation, at least not to the level where it could be a title threat.

The question now is whether the same simulation tools that sent it in the wrong direction four years ago with its initial car have now been sufficiently sharpened - and a huge amount of work has been done to improve them - or if there are nasty surprises lurking to catch the team out when it hits the track.

Mistake 2 - Tricked by false dawns

In the early days of the ground-effect regulations, Mercedes was adamant it would unleash the underlying performance it was certain was in the car. That set the tone for the search for breakthroughs, which led to what Wolff described as “false dawns” not because gains weren’t made but as a result of new troubles arising.

In 2022, a combination of the new front wing introduced at the fifth race of the season in Miami and a new, stiffer floor for the following race in Spain, appeared to have unlocked much of that promised car performance.

While the zero-sidepod concept worked well in isolation, it meant significant exposed and unsupported floor area. This moved too much and required stiffening because of what might be called a cantilever effect - effectively, there was more of the floor protruding beyond where it could be attached to the sidepod.

The Spain upgrade tackled that weakness. George Russell finished third and Lewis Hamilton charged from near the back to fifth after a first-lap clash with Kevin Magnussen’s Haas. James Vowles, then Mercedes strategy director, concluded that “we have a car that’s within touching distance of the front, and a car that we can fight for a championship with.”

However, new troubles were now exposed. The Mercedes W13 was conceived to operate at a low ride height but was now running higher, without the range of rear suspension travel required to optimise that. Running stiff as a consequence meant that while porpoising was no longer a big problem, the related phenomenon of bouncing was. The car also struggled in slow corners.

Russell won in Brazil late in the season, which was in itself an illusory breakthrough as it gave Mercedes confidence that an evolution of its troublesome ‘22 car would thrive in ‘23. It didn’t, failing to win a race.

There was another example of a false dawn during the 2024 season, when Mercedes introduced a flexible front wing at the Monaco Grand Prix. It had long struggled with finding a set-up that worked well across a wide range of corner speeds, which was one of the generic challenges of the regulation set.

If you have a powerful front wing, you have more front-end grip for the slow corners. The downside is that the faster the car goes, the closer the front wing gets to the floor and the stronger its own ground effect, giving more grip than can be matched by the rear, creating oversteer.

A more aeroelastic front wing reduced its effectiveness at high speed and unlocked more performance. This led to the strongest Mercedes spell of these regulations, winning three out of four races in the summer of 2024 - and only being denied a one-two at Spa after Russell was disqualified for being underweight.

Combined with changes made to the architecture of the Mercedes W15 for the start of 2024, including moving the cockpit position rearward having ditched the zero sidepods, it seemed Mercedes was back.

However, it was only a brief resurgence. Rear tyre temperature management and a narrow set-up window for a car that worked best in fast corners but struggled in slow turns then proved to be major weaknesses. That latter characteristic forced the drivers to use the throttle to help rotate the car, working the rear Pirellis harder.

Hopes that would be fixed with the ‘25 car proved wide of the mark and again the Mercedes, while quick, was only able to win twice.

Mistake 3 - Development errors

Errors in development direction interrupted the recovery progress of Mercedes in the ground effect era. The Mercedes W14 of 2023 - the only Mercedes that failed to win a race under these rules - is an example of that.

An evolution of the troublesome 2022 car, the error made with it was to conceive it to run at higher ride heights, rather than low ones where it was easier to generate big downforce levels. For 2023, the FIA introduced rule changes designed to reduce the chances of porpoising that included raising the floor-edge heights by 15mm.

The big decision for Mercedes was whether to continue to conceive the car to run low, or try to maintain the progress made late in 2022 and chase downforce at a slightly higher ride height.

Mercedes opted for the latter. And while the zero-sidepods were ditched with an upgrade at the Monaco Grand Prix in May, technical director James Allison later explained that “the conceptual change was all about undoing the conservative decision about ride heights” with a push towards chasing downforce at lower ride heights. The trouble is, by then significant ground had been lost and ‘23 was effectively a write-off.

Even in the final year of the ground effect regulations, Mercedes still had the capacity to trip itself up.

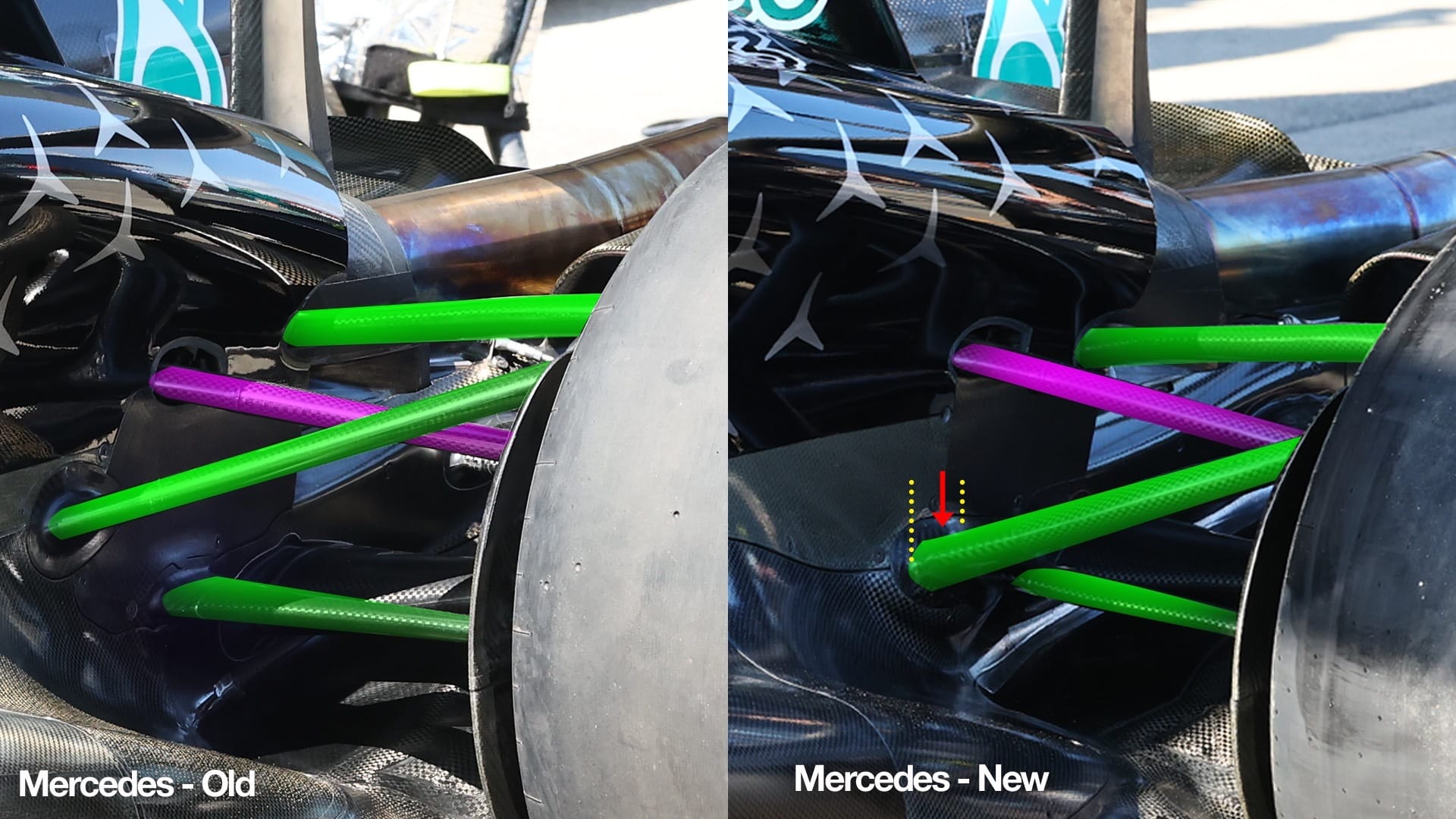

Having made significant gains with anti-lift in the rear suspension with the Mercedes W16 when it was launched in 2025, which is crucial for the mechanical platform control needed to optimise the aerodynamics, Mercedes attempted to take another step with the introduction of modified rear suspension geometry at Imola in mid-May.

“The big change that we introduced for Imola that we went back on was an attempt to go even further down that [anti-lift] route, but we then introduced other characteristics that were quite bad,” said trackside engineering director Andrew Shovlin.

“We lost a bit of stiffness in the suspension that was more penalising than we had expected it to be and that caused us to then backtrack and more or less go back to where we were at the start of the year.”

That the suspension was less in itself wasn’t unexpected, as it was the consequence of the modified installation, but it had a bigger impact on the car dynamically than anticipated.

Inevitably, it took Mercedes a little time to understand its upgrade was actually a downgrade. The rear suspension was on the car for the Imola weekend, then off again for the events that followed in Monaco and Spain. It then returned for Canada, where Russell won from pole as the straightline braking and short-radius corners didn’t expose the weakness.

The suspension continued on the car in Austria, Britain and Belgium before being removed for Hungary - as it turned out, for good.

Mercedes wasn’t the only team to make such errors during this regulations era - in fact, all teams had their troubles. But it contributed to keeping it on the back foot throughout.

Mistake 4 - Not copying others

Early in the 2022 to 2025 regulations cycle, Mercedes held firm in sticking with the concept it believed had the best potential. As Shovlin said in late 2022, “if you want to win races and world championships, you don’t get there by copying everyone else’s design".

That’s the correct philosophy, and he rightly stands by it, but Shovlin admitted in late 2025 that Mercedes should have been willing to be a little more adaptable in certain key areas.

“It's difficult to say ‘too brave’ because when we've won championships it's never been by copying, it's always been by innovating and I think if you try and criticise that culture of innovation and ambition, you'll end up with a team that might be a very solid also-ran, but I don't think you'll be winning championships,” said Shovlin in Brazil last year when asked whether Mercedes had been too bold.

“I think there were things where we could have least said we could have copied sooner, there were certain avenues of development that we could have got onto more quickly. We were perhaps being too analytical and overthinking it and a simple experimental approach would have given us more progress in the early stages of the regulations.”

However, Mercedes did improve on this score and show itself to be less dogmatic than it was early on. For example, in 2024 it switched from pull-rod rear suspension to the pushrod configuration, which was de rigeur among its rivals because it opened up greater aerodynamic opportunity at the rear of the car.

So has Mercedes learned its lessons? It’s often said in F1 that bad times can lay the foundations for success because a team spends so much time analysing its methodologies, tools and processes when things aren’t going well that it comes out stronger. And there’s no question Mercedes has gained a vast amount of knowledge.

Next year’s cars are different. They are no longer venturi-tunnel ground effect cars with the return of the step-plane floor and the expectation that ride heights will be higher - perhaps around midway between where they were in 2025 and in the previous rules era of 2017-21.

No knowledge is wasted in F1. After its years on top, Mercedes has been through a long, hard period of soul-searching and work.

Past failure is no guarantee of future success. But if Mercedes really has learned its lessons and poured that knowledge and know-how into its 2026 car, then if that’s paired with a leading power unit, it could be a very dangerous competitor.