Formula 1's all-new 2026 cars will be hitting the track for the first time in six months' time, when the official private test takes place at Barcelona next January.

While teams are heads down getting their designs together, there remains a great deal of uncertainty about just how the next-generation rules are going to play out.

And things have been further clouded in recent weeks with a couple of drivers offering some downbeat assessments of their experiences of the 2026 cars when trying them out on their simulators.

Lance Stroll labelled them "a bit sad if you ask me" as he suggested that the obsession with chasing more electrical power at the expense of out-and-out downforce had left F1 as a "battery science project" rather than being pure racing.

His remarks came after Charles Leclerc also labelled his first run in the sim with Ferrari's 2026 model as "not enjoyable".

These comments brought back to life fears that other drivers had voiced during early simulation running, when they too said the experience of the new cars was not great.

But with a lot of work having been done in recent months to address areas of concern, is F1 still facing the risk of disappointment with the all-new cars, or is the real situation slightly different?

The Race has spoken to the FIA's single-seater director Nikolas Tombazis to find out what the latest is with the F1 2026 cars, and what is really behind the drivers' comments.

A familiar critique

Driver unhappiness has been fuelled by two fundamental differences between this year's cars and what is coming.

The first is a lack of grip compared to now, with downforce levels in 2026 being reduced somewhere between 20-30%. This means the cars are going to be slower in corners.

The second aspect is drivers having to deal with energy deployment to a much greater extent - as managing battery power over each lap is going to be more complicated than now because the cars are not going to have an abundance of electrical energy on tap.

So, from Tombazis' perspective, the fact that the cars are slower in the corners, and require a bit of a different approach from the cockpit on the straights, makes it obvious that they will not be instantly liked.

"Clearly, if they jump out of one car that has a certain level of grip into another car that has less grip, I don't think they will ever say they prefer that," Tombazis said.

"Energy management is significant in the rules, there's no doubt about that. But we've worked a lot with the teams to make that a more transparent process to the driver.

"Some drivers have driven previous iterations of the rules. Some have driven more recently. We've also heard some drivers say positive things that they don't feel anything is dramatically wrong.

"I don't think we are ever going to get full marks and any statements that everything is perfect, because it is a change and therefore it will take some getting used to."

Tombazis also pointed out that drivers were also resistant to the 2022 rules initially, because they feared the cars would be five or six seconds per lap slower - whereas the reality is that they are now among the fastest there have ever been.

What the numbers say

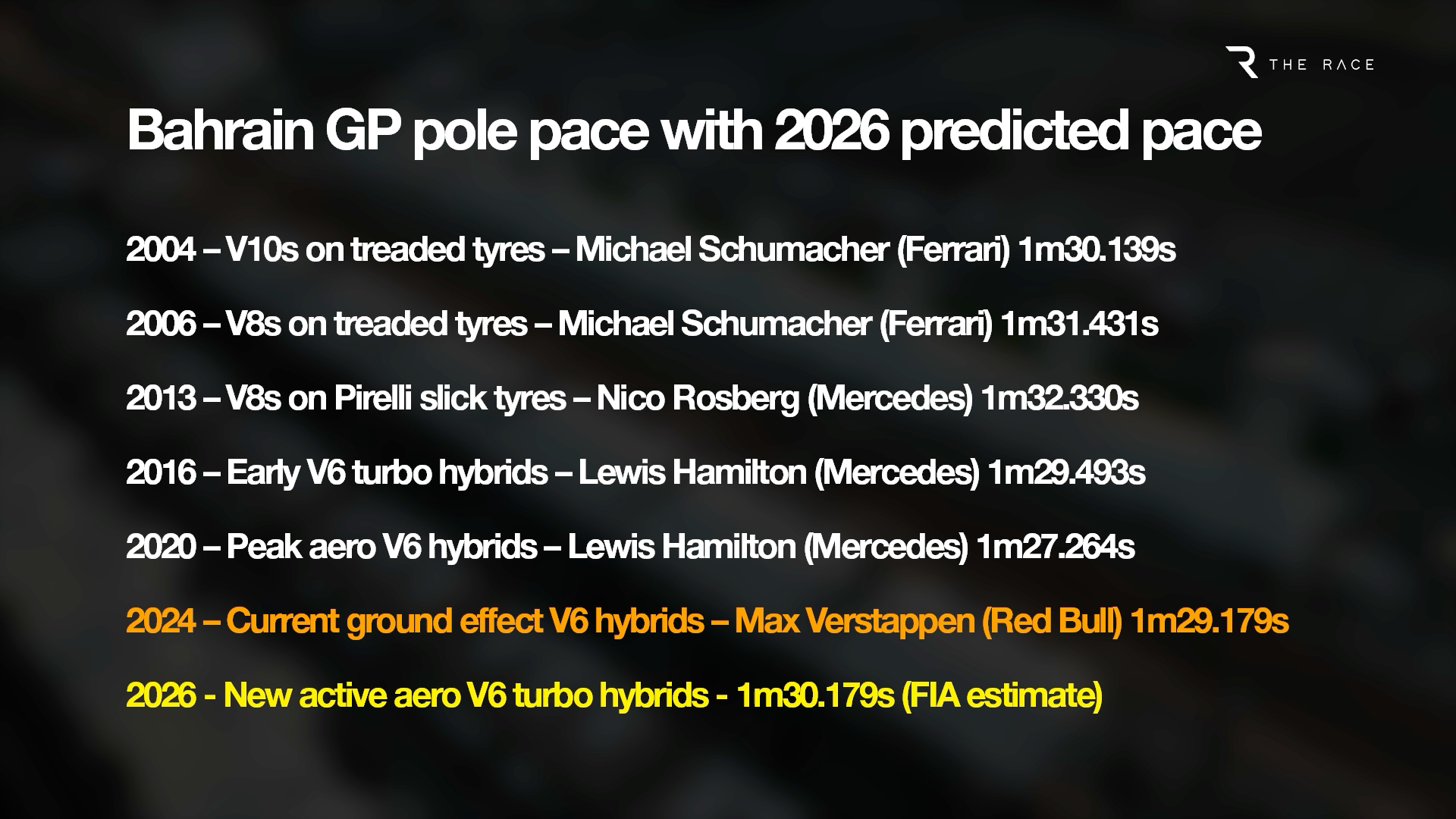

While the drop in downforce next year will be felt in the turns, the latest simulation data of the 2026 car shows that laptimes are actually not much slower than what we have right now.

Thanks to the cars accelerating quicker out of the turns - which punches them to a higher speed down the straights - the FIA's current prediction is for them to end up around one-second per lap slower than what we have right now.

It is also important to remember that F1 car performance is not something that stands still either, because teams are constantly working to improve their cars.

Tombazis said he expects that as teams get to grips with understanding the aero regulations they will quickly find more laptime so the gap between the new rules and what there is now will soon be wiped away.

His prediction was that by the time the 2027 season is underway, laptimes will already be back to the level we have right now.

There is also what one paddock figure has referred to as a 'twist in the tale' of drivers being potentially unhappy about having to race cars with less grip next year.

And that is a drop in performance should make some tracks - and especially some specific corners - much harder from next year, so there will be a bigger premium on driver talent making the difference.

Take Copse corner at Silverstone for example. With the current cars, it is easily taken flat in qualifying for every driver on the grid - so it is ultimately not somewhere that a good driver can make a difference compared to a lesser one.

In 2026, with a reduction in downforce, it will no longer be a full-throttle corner, and that means it will be down to the best drivers to extract the most they can from the car.

Energy management issue

There is no denying that management of battery power is going to become a big talking point next season.

This is primarily because, with the way the rules have been defined, at some tracks there is not going to be enough energy generated for the batteries to produce maximum power down the straights everywhere.

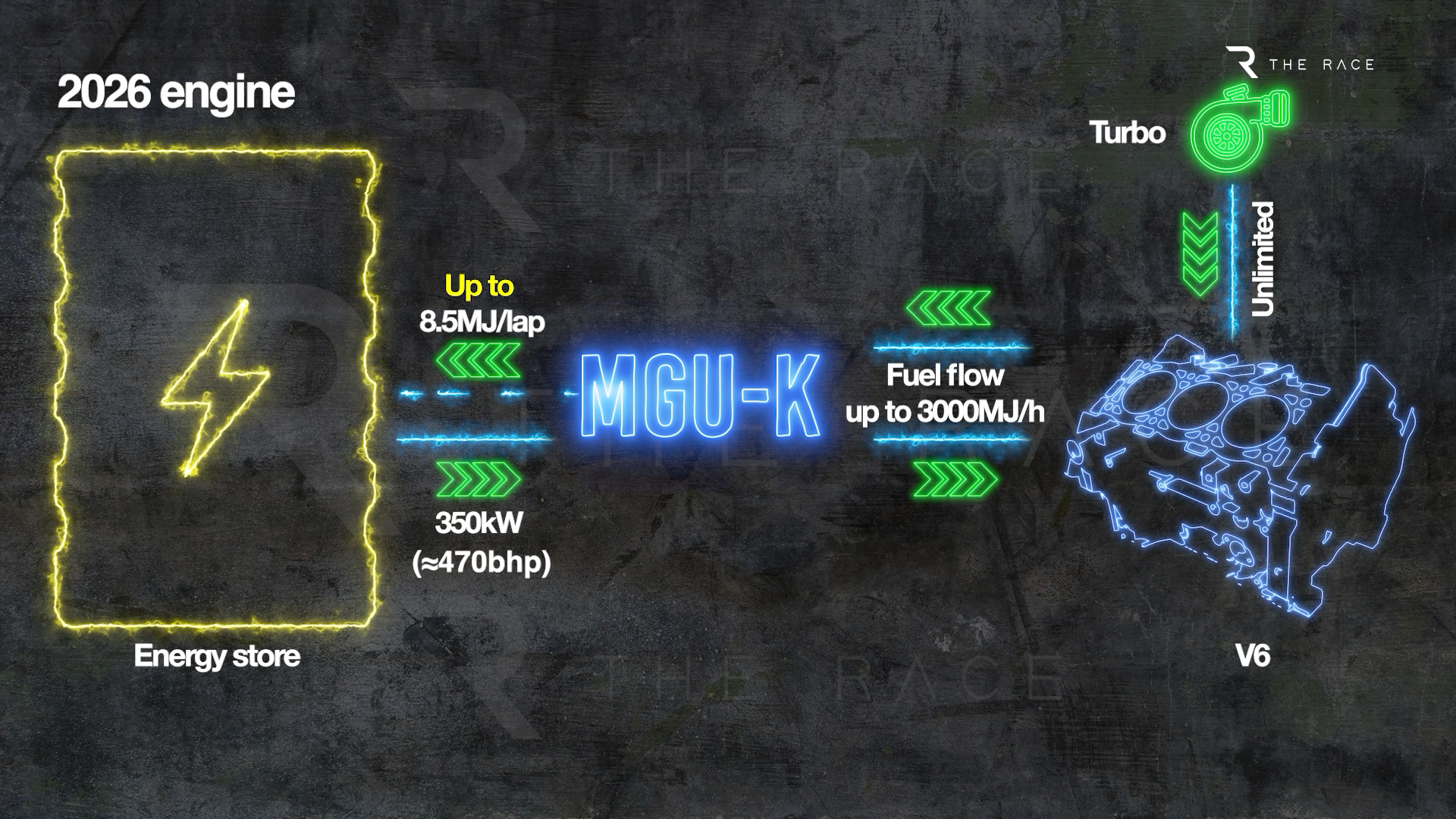

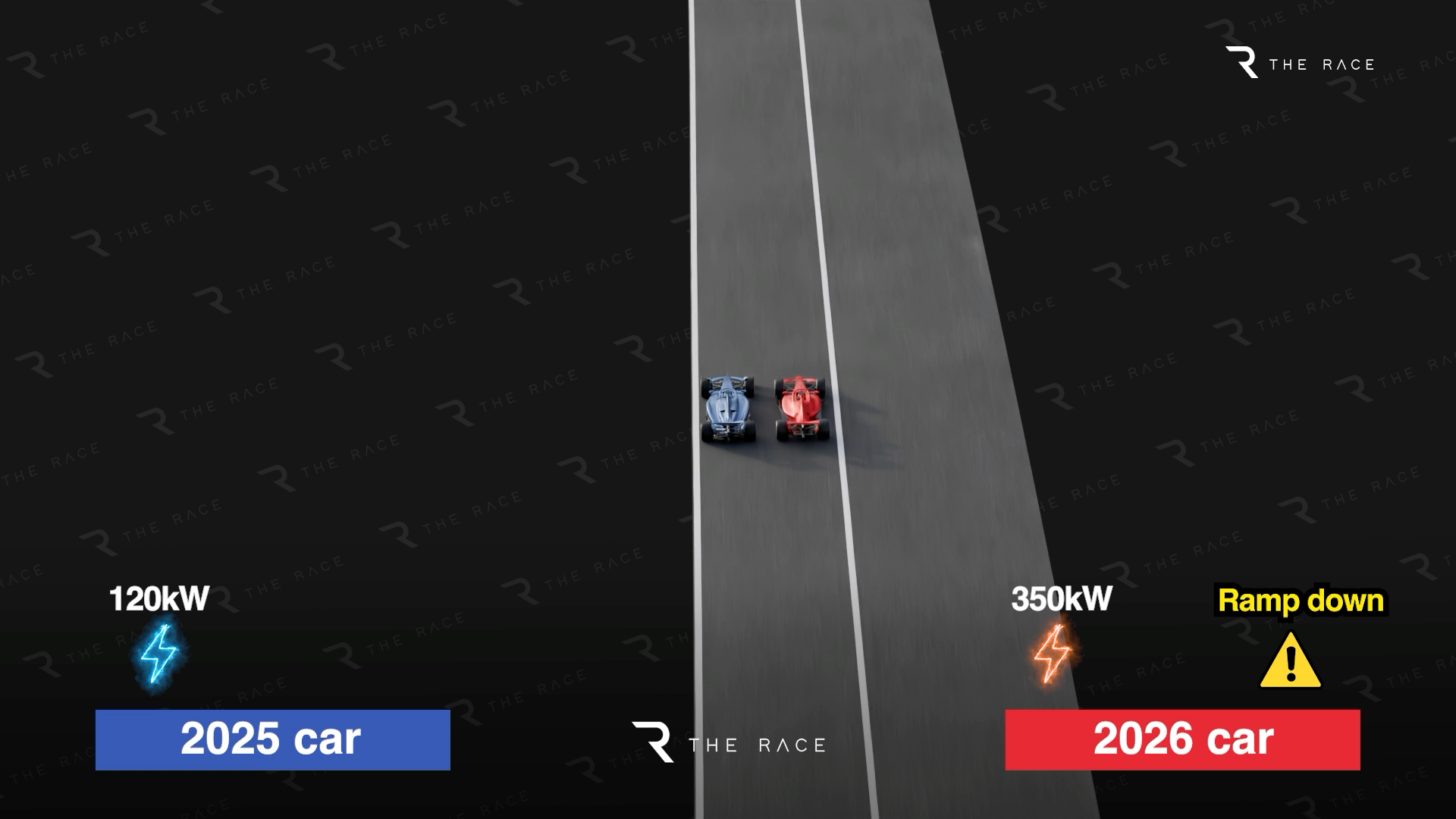

And it could be particularly noticeable because of the much greater reliance on battery power, which will deliver 350kW compared to the 120kW we have right now.

When the F1 2026 rules were in their infancy, there were plenty of Doomsday scenarios being predicted - which typically involved Monza and the fact that the cars could be running out of battery power halfway down the main start-finish straight.

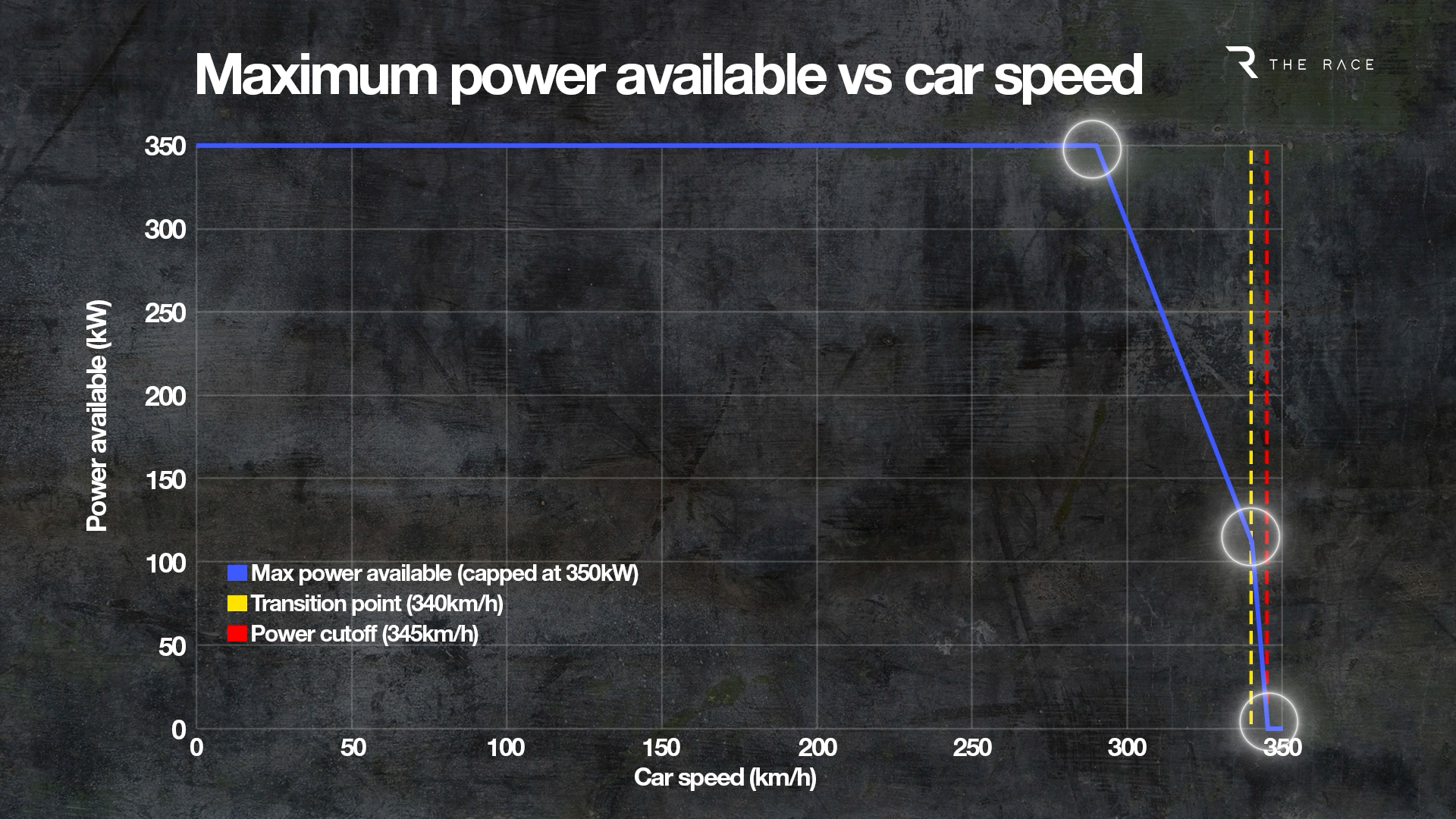

Efforts over the past 18 months have minimised the risk of that happening, which includes the low-drag straightline wing mode to help reduce the energy needed to push the car through the air, plus tweaks to energy power rules to prevent cliff-edge drops off of battery boost.

There is now the 'turn down ramp rate' that ensures a glidepath of power down from the maximum to zero, which should take seven seconds in total at some power-hungry tracks.

The FIA has been confident that these changes should be enough to address fears about cars running too short of power - but it has made further tweaks to help matters in recent months too.

This includes a recent change to the sporting regulations to limit the amount of energy harvesting that can be done at certain venues.

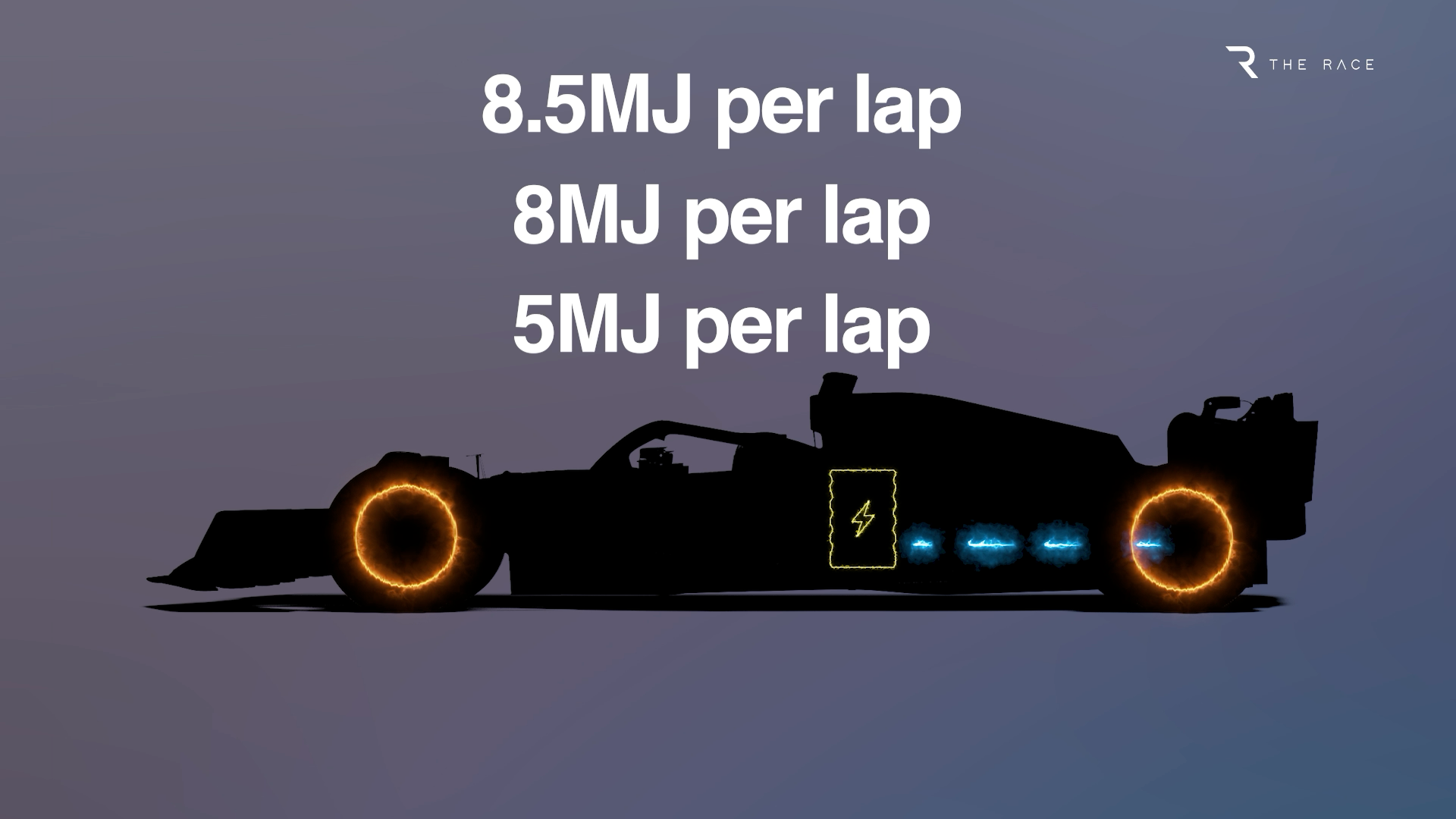

With it anticipated to be a challenge at some tracks without heavy braking zones to achieve the maximum charge of 8.5MJ per lap, freedom had already been put in the rules to limit this to 8MJ at some venues.

Now, however, an extra rule has been added that allows the FIA to pull this back to 5MJ when required as tracks that are more energy starved.

The regulations state that this will happen "at competitions where the FIA determines that the harvesting strategies required to achieve the above limit are excessive".

Tombazis has explained that the catalyst for this change was that the FIA did not want drivers to have to be forced into extreme behaviour on qualifying laps, such as having to brake hard on straights in random places.

"We wanted to make sure that for qualifying that we don't make it necessary for them to do any recharging on a straight," he said.

"The best way to do it is to say that the energy they can have is limited. Therefore they can obtain that energy in a more natural way, and not need to do any shenanigans on the straights or brake early, or anything like that.

"It is to protect qualifying - and to make sure that it is a pure expression of aggression, rather than energy management."

One other element that the FIA hopes teams will be open to is whether a move to limit power output in races should be reconsidered if there are energy deployment issues that affect the racing at the start of 2026.

Earlier this year, a proposal by the FIA to reduce the power from the standard 350kW to 200kW in races only ( it would remain unchanged for qualifying) - which would in theory help cars deploy their energy for longer - was rejected by the car manufacturers as they did not feel it was necessary.

While that is off the table for now, it is something that could be looked at again depending on how things shake up when the cars are seen in action for the first time early next year.

Tombazis said: "We believed it would have been a sensible step forward, and some teams also believed that, but it didn't get enough support among PU [engine] manufacturers.

"Of course, it is not a fundamental change requiring a redesign of systems. So we need to keep an open mind when cars start running and racing and so on, and at some stage, we may need to reconsider."

What still needs to be sorted

While much is now set in stone for next year, there are still some issues to resolve and grey areas to make more black and white.

One of the recent focuses has been on tidying up a few elements, such as ensuring that aero-elasticity tests are fit for purpose for the new cars where the moveable wings will make flexible bodywork tricks here less of an advantage.

Tombazis said: "There's certainly less benefit in having elasticity on the rear wings than there is now. But that is not completely absolute, so we do hope that things will improve.

"It will become less of an issue, but there are quite a few other forms of aero elasticity which are nonetheless quite significant for performance which wouldn't inherently be reduced [by moveable wings], such as floor flexibility and stuff like that.

"These will remain equally important. We do hope to make a step towards making it less of a talking point, but I don't think I expect it to disappear completely."

Some sporting regulations also need to be sorted out because issues have cropped up.

One of these, for example, relates about what to do in wet weather races if, on safety grounds, the low-drag straightline wing mode has to be disabled.

If this happens, then it means that the cars will be fixed in the high downforce corner mode throughout the lap.

This will not only have an impact on drag levels, but will add downforce to the cars when running down the straights, which will push them closer to the track and could risk them bottoming out.

Initial estimates say the difference between straightline mode being on and it being inactive could change the ride height by around 8mm.

It means a car that has been set-up without an extra margin for this height difference could be at risk of wearing its plank down if straightline mode stays off.

The FIA is discussing how best to get around this problem, with a solution most likely to involve a sporting regulation tweak that can be implemented very quickly.

Where 2026 cars will be better

While there remains uncertainty about many aspects of the 2026 cars, it would be wrong to suggest that everything is going to be a backwards step next year.

The new cars should be better able to follow other cars more closely, a trait that has fallen away since the most recent ruleset arrived in 2022.

The main idea behind moving to a ground effect concept was that cars relied less on clean air for performance - so in theory would not suffer as big a drop in downforce when running close behind another competitor.

But despite the FIA's best intentions, the rampant push by teams to chase downforce meant they started exploiting some areas of the car that brought back turbulent air and outwash, derailing many of the gains made.

Tombazis said it became clear early on with the 2022 rules that areas that should have been shut down had not been - such as the use of trick outwash elements on the front wings - but these have now been addressed for the 2026 ruleset.

"Since the 2022 regulations, we have learned a lot," he explained. "The cars currently are definitely worse in following than the 2022 cars were. No doubt about that.

"That is because of a number of areas in the regulations where teams started pushing the envelope and developing certain configurations that were not fully predicted or expected in the '22 regulations.

"By the time all of this happened, it was too late to make changes to the regulations, because we needed governance [approval].

"I believe we have learned quite a lot from that experience, and therefore, I think and hope this iteration will be much more robust in that respect.

"To know for sure, we have to wait until next year, but we do expect a significant step forward in the car's ability to follow other cars closely. We do expect them to be much, much better."

Revisions to the underfloor design, which will make the venturi tunnels less powerful, should also make the 2026 challengers less ride-height sensitive.

While the cars will still rely on some ground effect, they will not be as extreme as before - which is why some engineers have referred to them as effectively flat-bottomed.

Tombazis said: "There's a reasonably flat bottom. In front of the rear wheels, for a good portion, is much more flat. So I think it is fair comment there."

F1 teams have consistently battled against having to run the current cars super low to the ground, and with ultra stiff suspension, which has left engineers feeling a bit cornered in terms of what they can do with set-up.

As Mercedes technical director James Allison once said: "I'm sure I bang on about this because it's been a bugbear of mine, but I personally don't think it's a great thing.

"I don't think it's good having the cars operating, when they leave the garage, with that much space [signalling a few millimetres with his fingers] to the ground."

Tombazis said that the aim of making the 2026 cars less ride-height sensitive appears to have paid off based on early feedback, as they are set to pitch somewhere between where the 2025 cars are now and where cars were in the pre-ground effect era.

"For '26, we believe that cars will typically still be more performing from a purely aerodynamic point of view, if they're close to the ground," he said.

"But the slope that the rate at which they improve as they go closer to the ground, we believe, gets reduced by quite a significant factor.

"As a result, we believe that the optimum will be more naturally a bit higher. Some of the indications we get from teams is that this objective is likely to be achieved.

"What they are finding is that it's considerably less sensitive to ground clearance, and more likely to lead us towards a slightly higher condition to alleviate that problem.

"I don't think we're going to get to 2021 levels of static ride height, but I think we can be quite optimistic that we'll be higher than where we are now."