Up Next

For all the turbulence inside the team, Red Bull’s races have rarely gone so smoothly as the 2024 Saudi Arabian Grand Prix, Max Verstappen and Sergio Perez recording a 1-2 every bit as serene as that of Bahrain.

There was a stress-free gap between them which needed no management and Checo was able to pull out enough distance on Charles Leclerc’s Ferrari that he comfortably overcame a 5s penalty incurred by an unsafe release from his pitstop.

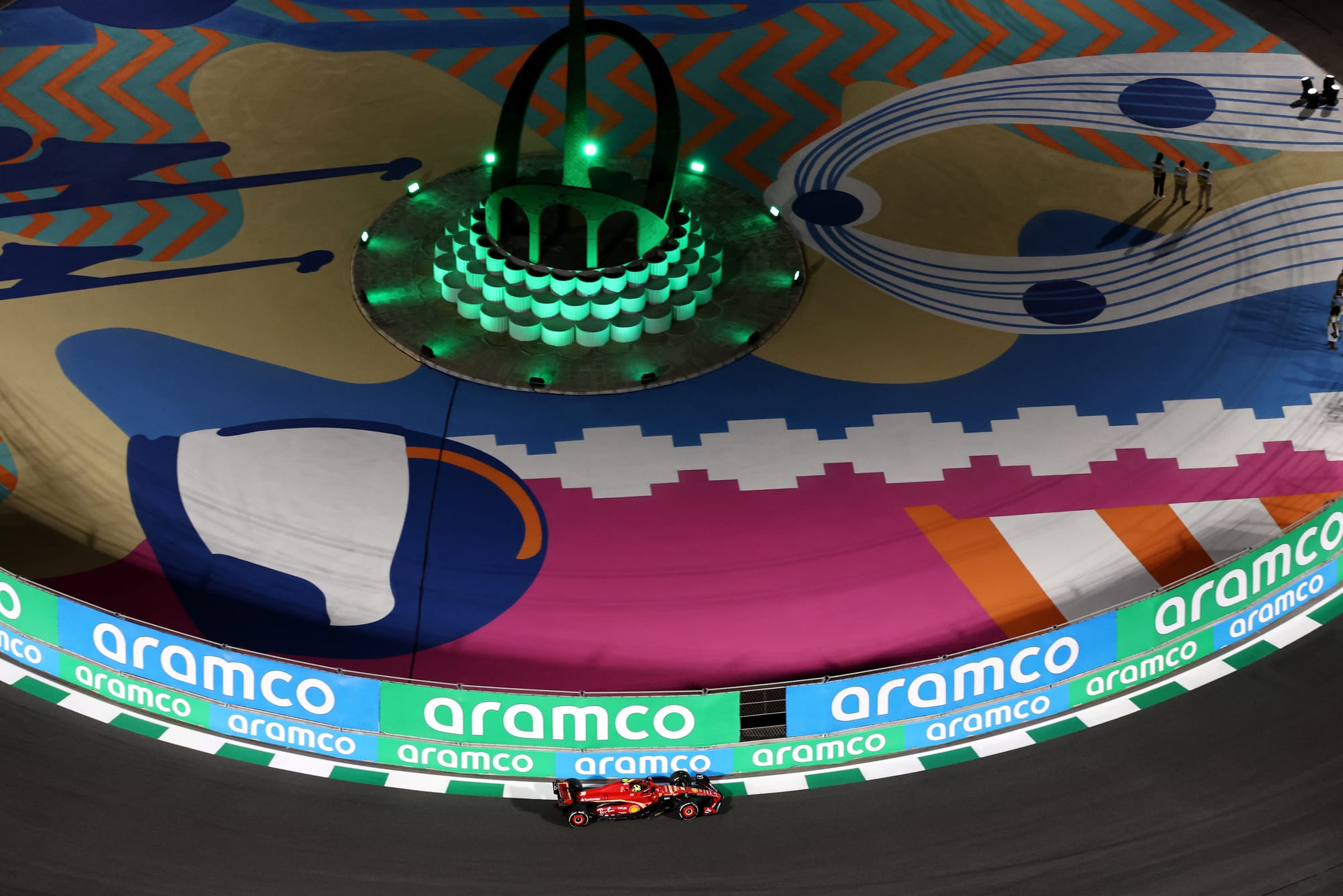

There’s something anomalous about the super-smooth on-track performances of Red Bull and the upheaval inside. Just as there is between a flat-out race around such an exciting, heart-in-the-mouth track as Jeddah being so uneventful.

It probably didn’t feel that way for 18-year-old Oliver Bearman, performing a quite brilliant short-notice stand-in role at Ferrari for an incapacitated Carlos Sainz and finishing a strong seventh. But that aside, it was an unremarkable race.

“The crazy thing was how hard you could push,” said Bearman of his first impressions of an F1 race. “Especially in those last 10 laps when I had the guys [Lando Norris and Lewis Hamilton] coming up behind me on softs, I was basically doing quali lap after quali lap after quali lap.”

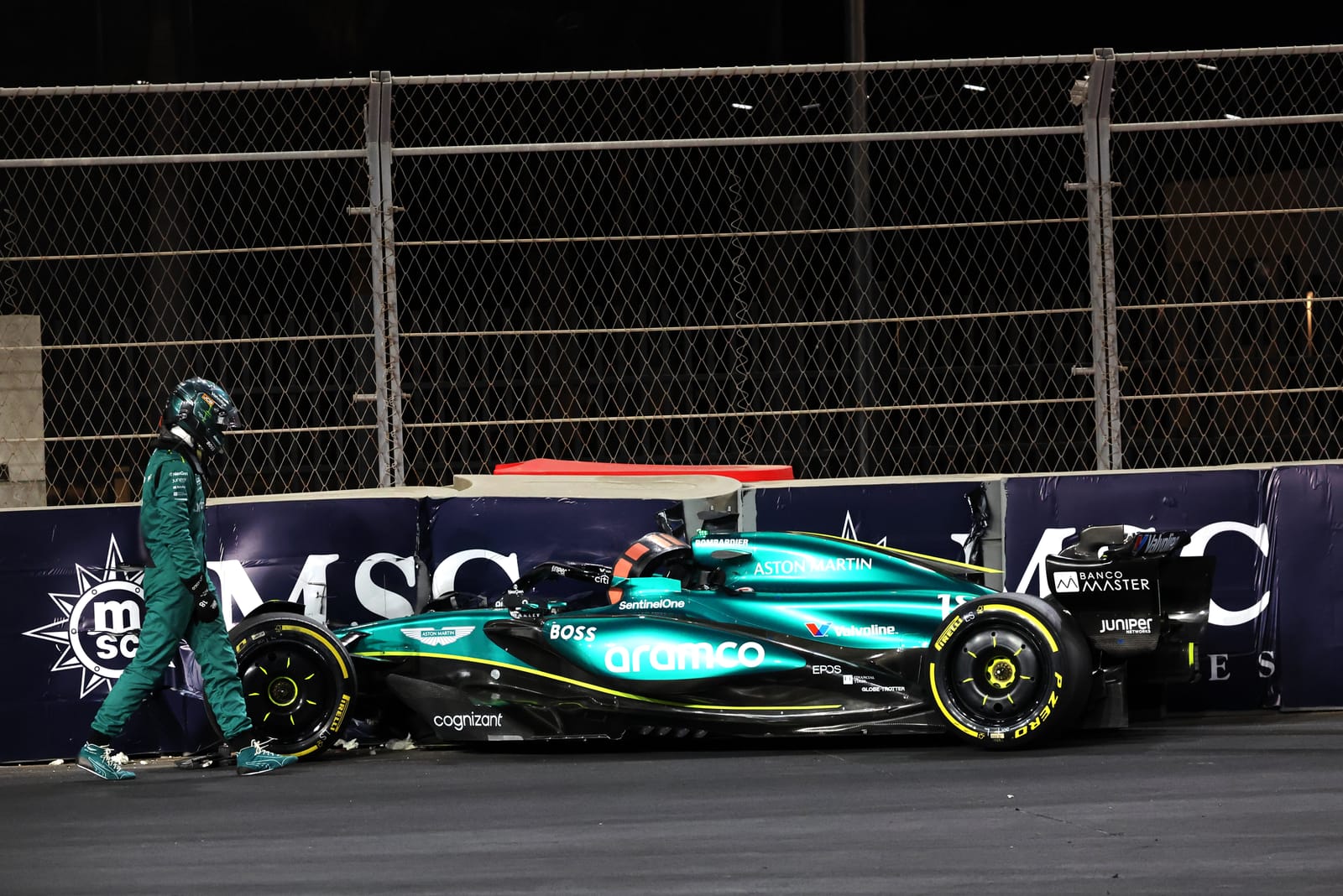

It isn’t usually like that, of course. Only sometimes. But it was a function of the very low tyre degradation from a circuit which doesn’t impose anything like the stress on the rubber of Bahrain and a fairly conservative selection of compounds by Pirelli. The lack of tyre degradation wiped away any differentiation of tyre pace, something which the lap seven safety-car (for Lance Stroll’s crashed Aston Martin at Turn 22) only further ensured.

With the exception of Norris and Hamilton (and two others in the lower half of the field), everyone came in at the same time, taking advantage of the 10s saving in pitstop loss. It being so early in the race, everyone also switched to hard tyres so as to get to the end, so no variation there either.

That low degradation is what encouraged most to make their only stop with 50 laps still to go. Even the medium could probably have done the full distance. If everyone had stopped at the same time even if the safety car had happened on lap one it wouldn’t have made any significant difference. Six more laps on those tyres was neither here nor there. If it had happened at 20 laps probably that wouldn’t have made a difference either!

It turned out you were better coming in than staying out. But that was only because everyone came in! All the cars which stopped were running in the same order they started. But if half the cars had stayed out and you were running with six or seven cars of traffic in front of you, staying out would have been much worse.

Conversely if, say, Oscar Piastri (who finished a good fourth for McLaren) had stopped and no-one else did he’d have dropped to 18th and would have been waiting for everyone else to get out of the way, which if everyone went as long as Hamilton did (to lap 36), would have been a disaster for the early stop. You’d never make all those places back up.

The best thing to do was the same as what the majority did. Because the track position and its impact re traffic was worth way more than anything else and the very low tyre deg was the main reason for that.

Norris and Hamilton (plus Nico Hulkenberg and Zhou Guanyu) stayed out because otherwise they’d have been stacked behind their team-mates in the pits, as they’d been running close behind them. So that committed them to their long opening stints on their mediums. It didn’t pay back.

Norris and Hamilton rejoined on soft tyres a few seconds behind Bearman but so quick and consistent was the rookie and so low his tyre deg that they couldn’t reach him before the flag.

Low deg and an early safety car were two of the reasons for the lack of variety. Another was the unusually clear differentiation of the cars in the front half of the field, with step changes between each.

It’s normal for Red Bull to have an advantage of course. But the Ferrari was very clearly the next best, comfortably faster than the McLaren which in turn had a significant edge on Fernando Alonso’s Aston Martin which could keep George Russell’s Mercedes behind it all race.

The Mercedes was the slowest car of all through the fast kinks of Turns 6-10. It was going through there 7km/h (4mph) slower than the Alpines, 11km/h (7mph) slower than the Red Bulls and Ferrari.

Running at the super-low ride heights seen at the high speeds reached here is triggering the Mercedes into an all too familiar bouncing problem, which was making it a handful. It was running a low downforce wing and was quick on the straight. This allowed the out-of-sequence Hamilton to keep himself ahead of Piastri whose McLaren was poor through the slow corner onto the pit straight and at the end of the straights.

But it wasn’t really for position as Hamilton, like Norris (who always ran a few seconds in front), had still to make his pitstop. When he did so it released Piastri into fourth, albeit some way distant from Leclerc.

Alonso was able to keep Russell’s Mercedes behind him and once Bearman had fought his way by Yuki Tsunoda and the long-running Nico Hulkenberg, he was running a few seconds behind them and running the same sort of times.

Norris – who led the race from the restart and kept Verstappen behind him for a couple of laps – came out from his eventual stop around 6s behind the rookie in the Ferrari. He and the closely-following Hamilton closed him down, but not by enough. With a bit of reassurance from race engineer Riccardo Adami, Bearman confidently stepped up the pace like he’d been doing this for years.

Behind Hamilton, Hulkenberg took the final point. He owed his Haas team-mate Kevin Magnussen heavily for this, Magnussen having bunched and slowed the chasing pack of Williams, RBs and Esteban Ocon’s Alpine for long enough to create a gap for Hulkenberg to drop into after his pitstop.

Verstappen had to thread his way past a few of the backmarkers in the late stages on very old rubber, giving him the odd anxious moment. But other than that, his 100th career podium could hardly have been more routine.