Formula 1’s 2026 cars are tipped to unleash some big overtaking surprises.

As design work gets ever deeper, and simulator models become more sophisticated, teams are discovering that the racing may be totally different to what it is like right now.

A lot has already been said about the way battery energy will need to be carefully managed next year, with the new power units featuring a 50/50 power split between the internal combustion engine and electric.

But how teams approach new active aero elements is also going to have a more significant impact than originally anticipated.

This is why Aston Martin team boss Andy Cowell has teased that “there will be surprises” on this front.

The suggestion is that overtaking will be more frequent, and it may well be happening in places where passing is not so common right now.

But while that may sound exciting, it does not come without risks.

New passing places

As teams have begun working on their simulations to try to get a better understanding of how the racing will shake out, some fascinating scenarios have opened up.

This is a consequence of drivers often not having access to full battery power for every straight around a lap.

This means they are going to need to be smart about where they deploy it, and even where they choose to use the new override mode - which is effectively an overtaking boost button that hands them some extra available energy.

Williams boss James Vowles has suggested that at current tracks where there are just one or two obvious overtaking opportunities - like Spa-Francorchamps’ run to Les Combes - the door could be open for drivers to use extra energy to dive past rivals in different places.

“I think you’ll move away from, say, Spa - where your typical overtaking point is, for example, up into Turn 5,” he said.

“Actually, it opens up the door for a few other areas around that lap."

Potential speed differentials on offer with override mode could open up chances on several other straights - such as the run down to Pouhon or even through Blanchimont into the chicane.

This could be especially true if drivers ahead are tricked into burning too much energy in the wrong place around the lap.

But even those drivers attacking from behind and wanting to make progress are going to have to be smart about where they pull off their moves.

It will be of no use in burning up all your battery power and override mode capability down the start-finish straight at Monza to pass a rival, for example, if you are then going to find yourself a sitting duck coming out of the first chicane.

Drivers may also find themselves having to be clever when it comes to picking the places where they want to harvest energy and where they want to deploy it.

It may no longer be a case of every straight being about going for maximum power.

One scenario that has been suggested is that in the short blast between the first and second Lesmos at Monza, drivers may find that they are better off backing off there to harvest some energy rather than going flat out.

This will then give them more energy for deployment for the run down to the Ascari chicane, where they can carry their speed for longer.

Drivers may have to accept getting swamped by other cars if they are harvesting energy while others choose to deploy it - but the flip side should be that they are able to retake positions later on.

At some locations, however, drivers may find themselves with no choice but to burn through their energy because there may not be a chance later in the lap to retake the place.

One such place could be the Monaco tunnel - where if you lose a position because you are saving battery power, then you may find yourself stuck behind your rival for the rest of the lap.

The 'complex' new aero factor

The new energy deployment rules are already enough to change the nature of overtaking in F1 next year - but there is another extra element that could shake things up even more.

It is that there is going to be a big variation across the grid in terms of how much energy each car is going to have available - and this will be a consequence of both different power unit designs but also each team’s aerodynamic approach.

When F1’s 2026 cars hit the track for the first time, there is likely going to be quite a bit of variation between the different engine manufacturers.

Those who have nailed the rules may deliver their drivers not only a more powerful engine, but also one that perhaps recovers its energy quicker and better than others.

This could allow them to have extra battery power on tap around the lap, which would be critical in both boostinglap time and also overtaking any rivals who find themselves out of energy as they have already burned all theirs up.

But there is an extra element that has emerged as teams have begun working on their 2026 designs - and this is the choice of wing levels.

Where teams choose to pitch their downforce and drag levels could have a huge impact on overtaking, too.

F1’s decision to go down a moveable aerodynamic route was because it needed to reduce drag as much as possible down the straights in a bid to help the cars not burn up their battery power so fast.

But it is wrong to think that the moveable aero will work in a way that it sheds drag completely - because it is not as if the wings are going to go completely flat.

Instead, the moveable flaps are going to operate in a similar way to how current DRS works - where the upper flap flips up and sheds approximately two thirds of the drag and downforce.

With the front and rear wings changing from straightline mode to corner mode throughout the lap, teams are going to face a call on where they want their downforce and drag levels to be.

The ideal scenario is for the wings to deliver maximum downforce in the corners while switching to minimum drag on the straights.

But the reality is that teams are going to have to choose a compromise between those two - because it is not possible to have the best of both worlds.

The headache will be that a car that has its wings pitched more towards downforce for better cornering will have more drag, even when its straightline mode is activated.

It will therefore be slower down the straights, and will need to use more battery power to punch a hole through the air.

But on the flip side, a car that has its wing pitched for minimum drag down the straights will probably find itself exposed by suffering in the corners as the downforce levels will not be as high.

Get your wing levels wrong in either direction and you could find yourself exposed to being passed easily on the straights, or find rivals muscling their way past you into or through the corners.

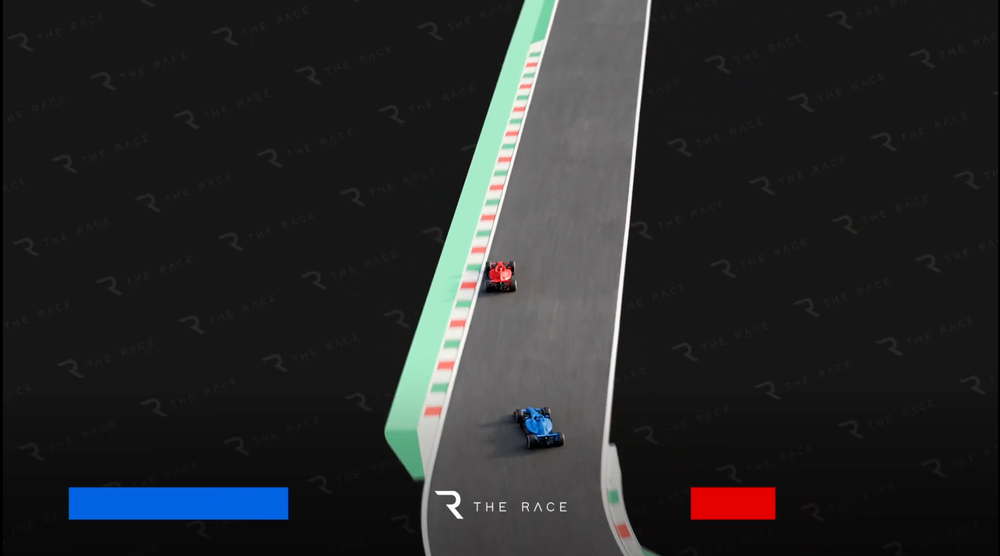

There is also a scenario that if teams choose very different approaches - one goes for higher downforce and the other for less drag - then they could be swapping places several times per lap as their strengths and weaknesses play out.

One car could be quicker through Monza’s Parabolica, for example, because they have more downforce, so they can sweep around a rival.

But with greater drag, and through burning up more energy on the following straight, they could find themselves passed quite quickly.

It is no wonder that Alpine technical director David Sanchez has admitted that matching the right wing levels to energy deployment for the best performance was far from easy.

“Straightline mode, if you were to compare it to DRS now, it’s not too dissimilar,” he said.

“But what adds a lot of complexity is the coupling to the energy management. This is where next year's car in terms of aero efficiency, matching straightline mode and energy management, is a very complex problem to solve.”

A moving target

There is not one element with the 2026 cars that stands out as the magic bullet in opening the door for a different approach to overtaking.

It is more about how a combination of elements have come together - and some of these even remain a moving target.

For example, the locations and durations of the activation zones - where override mode can be deployed and active aero modes switch - will be decided on a race-by-race basis by the FIA.

Furthermore, the necessary gaps between cars at the detection zones that will enable everride mode to be activated will vary at every track, too.

How aggressive or conservative these are could make all the difference in determining how powerful override mode is.

Get it right and there could be a decent power offset between two drivers battling - especially as there are separate regulations that dictate a ramp-down rate for each car on the straights.

So if a pursuing driver times the activation of their override mode perfectly, they could well enjoy a couple of seconds more boost than their rival whose power is declining - allowing them to easily blast past.

Too much overtaking?

Based on what we know so far, F1 could turn into a game of cat and mouse when it comes to overtaking next year.

On paper that sounds great, as after years of being starved of much overtaking there could be no shortage of action in 2026.

But if things do get a bit crazy next year, and cars are overtaking each other several times per lap, then that risks opening the door for something that proves too chaotic to follow.

If there is too much swapping of places then overtakes could become meaningless - and that is as big a turn-off as when passing is a rarity.

This was one of the complaints in the early DRS days, when F1 sometimes made it too easy for following cars to get past.

What will be key is for the FIA to ensure that it positions the detection and activation zones in the right place for each track - so that things do not become too much of a lottery.

The likelihood is that the start of 2026 will be a huge learning exercise for everybody, though, and that means there is plenty of scope for those surprises that Cowell has talked about.