Seven F1 eras ending at the 2025 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix

Sunday’s Abu Dhabi Grand Prix doesn’t just mark the end of a Formula 1 season but several significant partnerships too.

From one of the championship’s most successful engine manufacturers to the last race for one of F1’s greatest underdogs - here are seven eras ending this weekend, our thoughts on how successful they were and what kind of high (or low) they’ll likely end on.

Yuki Tsunoda + F1 (2021-2025)

Yuki Tsunoda went far further than most Red Bull juniors, of which there has been a truly astounding amount, and stuck around in its F1 roster far longer than many of his high-rated peers. The Honda patronage has played a part in both, but so did Tsunoda's obvious prodigious talent - which at 25 still probably hasn't been tapped into fully.

He has succeeded in going this far. But he is ambitious enough not to feel his time as a Red Bull-backed F1 driver has been a success - and it almost certainly ends here, even though he remains on the books as a reserve.

Triple-digit starts - a new high watermark for a Japanese F1 driver - but no podiums, much less wins. And just as Toro Rosso-turned-AlphaTauri-turned-VCARB-turned-Racing Bulls got probably its most podium-capable, most compliant car, he headed off to get blown out by Max Verstappen at the senior team.

He'll feel he deserved more on the evidence of the final few rounds this season - and could yet add to that in Abu Dhabi, though podium contention would be a shock - but he got more time than is often afforded within the Red Bull structure. - Valentin Khorounzhiy

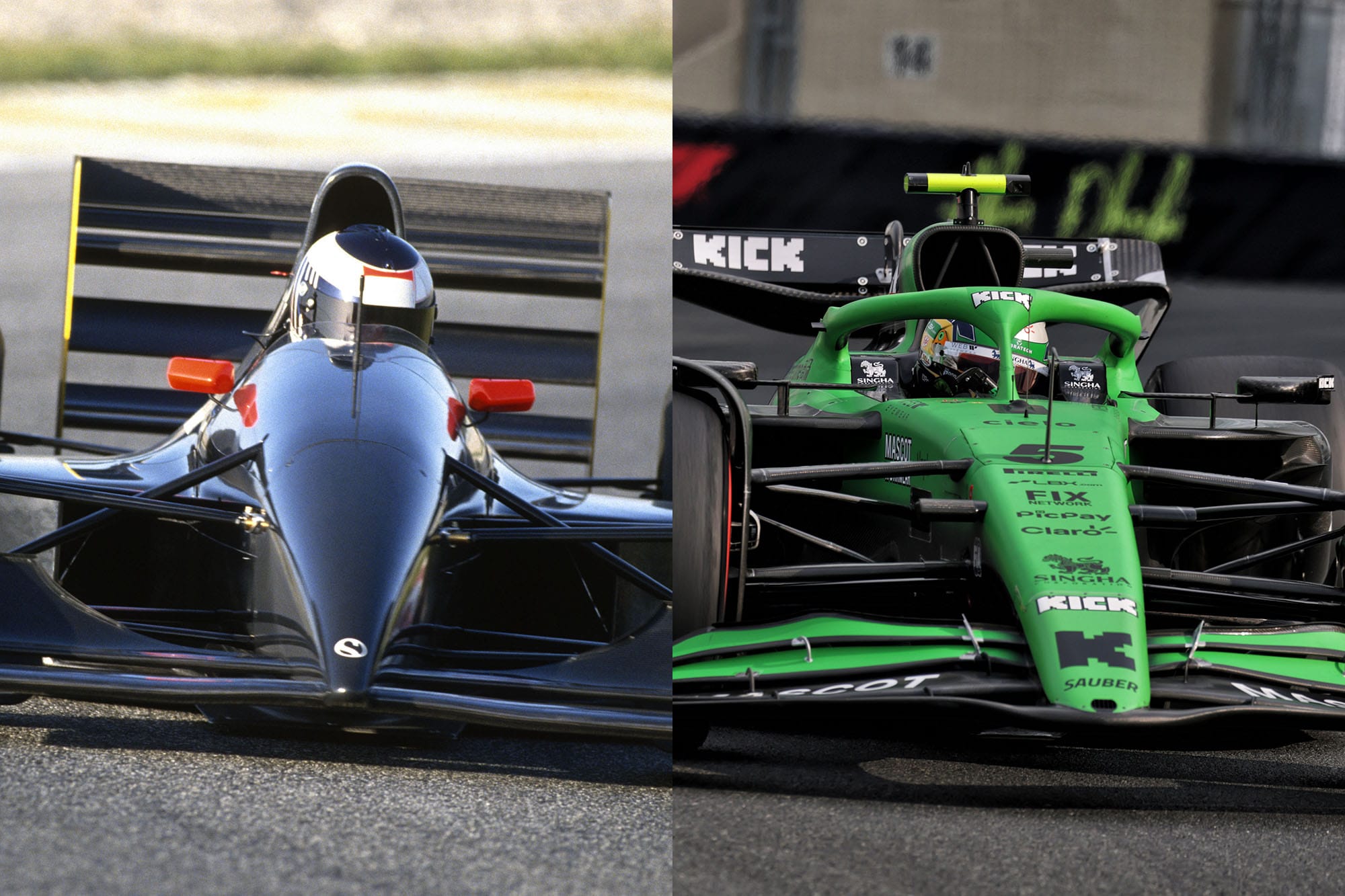

Sauber (1993-2025)

The Sauber name has been an ever-present in Formula 1 since it marked its debut in the 1993 South African Grand Prix by running fourth and fifth at the end of the first competitive lap.

Even when marginalised in 2006-2009, the team still competed under the BMW Sauber title, with Peter Sauber retaining a 20% stake. However, in F1 Sauber will be fully subsumed by Audi next year.

When the Sauber F1 project started, it was as a Mercedes factory team. Yet even when the three-pointed star backed out in 1991, it continued as an independent and built a reputation as a pragmatic operation. It lacked the flamboyant risk-taking of a Jordan Grand Prix, but established itself as a rock-solid midfielder.

In its first 13 seasons in F1, it bounced around between fourth and eighth in the constructors’ championship, never great, but never at the back.

However, canny moves such as selling Kimi Raikkonen to McLaren and building a state-of-the-art windtunnel set it up for a manufacturer future, as BMW took it over in mid-2005.

That alliance was shortlived given BMW pulled out ahead of 2010, but yielded a famous win for Robert Kubica in Canada 2008 as part of an unfulfilled flirtation with a drivers’ championship bid.

A sale to Swiss-based Qadback was agreed and announced, but fell through, leaving Peter Sauber to pick up the pieces and keep the team going. He didn’t need to, but he was driven not only to ensure the team he built survived, but also out of a noble sense of responsibility to its home town of Hinwil.

Sauber’s survival was uncertain and results patchy in the years that followed, and even after Longbow Finance bought the team in mid-2016 progress was stuttering. But after various possible deals fell over (remember the Honda engine deal, or the near-takeover by Andretti?), and after a stint carrying the Alfa Romeo name in a glorified sponsorship deal, Audi agreed a deal for a phased takeover of Sauber 2022.

Sauber has endured when it could easily have gone out of business after BMW’s withdrawal, or never even made it to F1 in the first place after Mercedes pulled the plug. In that context, it’s a remarkable story that this team heads into what could potentially be an illustrious Audi era after the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix. - Edd Straw

DRS (2011-2025)

Imagine telling any hardcore fan understandably put off by the inevitably gimmicky, un-meritocratic nature of the Drag Reduction Systrem and its arbitrary one-second trigger point: "Don't worry, it will only stick around for...oh, 15 years."

But here we are 15 years later, with DRS about to be phased out for an activate-at-any-time active aero and the more overtaking-focused 'manual override' battery power boost, and it doesn't really feel like the idea has outstayed its welcome all that much.

DRS never became less artificial, and DRS overtakes never became much more exciting, but with more lasting Pirelli tyres, regulations that allowed the downforce numbers to spike and F1 teams constantly outdeveloping the FIA's efforts to mitigate dirty air, F1 racing grew unimaginable without DRS, the alternative a dystopia in which every other race is basically Monaco.

That is, perhaps, no great argument for DRS as much as an argument for something being fundamentally off on a wider scale - but it's telling that other series adopted it, and that F1 drivers' feedback from the Qatar race last time by, as it has been in multiple rounds over the years, was 'they probably should've extended the DRS zone'.

Perfect? Nope. Desirable? Not particularly. A bandaid that held on for 15 years, and will continue in spirit? You could say that. But at least there was racing. - VK

Red Bull + Honda (2019-2025)

Honda's most successful F1 era ever comes to an end this weekend, so even though the manufacturer will live on in F1 with its new Aston Martin venture, a very significant chapter is coming to a close.

The Red Bull-Honda era effectively began in 2018 at Toro Rosso, off the back of Honda's acrimonious split from McLaren, before the main team took the plunge too a year later. Neither party could have imagined it would play out this well.

Honda has won almost as many races in its Red Bull era (71) as it has its entire previous history in F1 (72), which started in 1964. They have won four straight drivers' titles together, and the constructors' championship twice.

And there are three specific aspects to consider within this. First, the success. Without each other it is hard to imagine either party ever winning in this era the way they have. For both Red Bull and Honda this has been a transformational alliance.

Second, the Max Verstappen-Honda alliance. Verstappen quickly came to love Honda, and has been adored in return. Senior Honda figures talk about him in the same breath and with the same warmth as Ayrton Senna - so that relationship formally ending is a significant moment.

Last, but not least, remember it is the final race for the second Red Bull team with Honda. Without that team, history could be very different. It was in the team's Toro Rosso era that it ended up the Honda-powered guinea pig ahead of Red Bull's full switch - and that set a great foundation for the working relationship.

Honda has never forgotten the role what’s now Racing Bulls played in setting up what followed. - Scott Mitchell-Malm

These ground effect F1 cars (2022-2025)

This is the last weekend for this shortlived generation of ground effect F1 cars and, for some, it’s a case of good riddance.

Ferrari’s Lewis Hamilton is one of those drivers who is “excited to see the back end” of the cars. Williams’s Carlos Sainz is another; he said it’s “not in his nature” to drive these cars, and it’s been a struggle to adapt.

This is F1’s heaviest generation of cars, and some drivers (like Hamilton) particularly hate the ground-effect car’s race-ruining transition from understeer to sudden oversteer.

Porpoising wasn’t a great experience, either, with Mercedes’s George Russell calling it a “brutal” trait.

Health issues aside, F1 cars shouldn’t be on rails. They should require a great deal of skill to pilot, and they should look and perhaps feel to be on a knife-edge.

As a result, the midfield has hit spec-series levels of split timing and 2024 was a pretty great season as F1 goes. This season hasn’t been vintage throughout, but at least we’re down to the wire with a three-way title fight.

Sauber’s Nico Hulkenberg (who broke his podium duck in 2025) was less scathing about these regulations, although he criticised how difficult it is to overtake. Which is understandable, given F1 teams have inevitably engineered outwash back into the cars.

Williams’s Alex Albon defended this era when he said: “There are some elements where it's easier to overdrive these cars than maybe the previous generation of cars, but I think all in all it's not been a bad regulation set.”

We weren’t left wanting for tech stories. Mercedes’s zero sidepod concept and subsequent struggles; Ferrari’s wild upgrade ride; Red Bull’s fall; and McLaren’s rapid rise among them.

It’s been one of the better eras in that regard. Above all, this version of ground effect will be remembered for its finale - however that may materialise. - Samarth Kanal

'Team Silverstone' + Mercedes (2009-2025)

Aston Martin and Mercedes’ partnership ending might feel insignificant, but when you do the maths, this pairing has actually been together 17 years!

Force India - Aston Martin’s previous-but-one incarnation before it was named Racing Point - only did one year with Ferrari engines in 2008, before switching to Mercedes, which has powered the team through various guises ever since.

That was a landmark deal at the time with McLaren supplying Force India with Mercedes engines, gearboxes and simulator time, essentially the pioneering blueprint for a modern F1 technical partnership.

It powered Force India to plenty of giant-killing successes in the 2010s, a race win under the Racing Point guise in 2020 once Lawrence Stroll had taken over, and Aston Martin’s ups and downs ever since then.

The Aston Martin team has placed a lot of resource and hope in signing Honda for 2026 and it will hope it makes a big step forward. But the engine was never the weak part of this partnership so Aston Martin has a lot to prove heading into the next rule set.

Only once this season has Aston Martin gained the points in a single weekend that it would need to overhaul Racing Bulls for sixth in the constructors’ in Abu Dhabi. So instead it’s last Mercedes-powered weekend is likely about consolidating its seventh place, with Haas seven points adrift. - Jack Benyon

Farewell Renault F1 engines (1977-2025)

Gary Anderson

I will actually be a bit sad to see the Renault engine disappear from F1 this weekend.

I was around when Renault introduced its V6 turbo in 1977 - it was great to see someone do something different. In the early stages, it wasn’t without its problems and a fair few people were sniggering at Renault’s efforts. However, Renault got it under control quickly and as a Renault works team, it won the French GP in 1979. Renault went on to win three races in 1980, three in 1981, four in 1982 and four in 1983 when it also finished second in the championship.

It was also a power unit supplier to Lotus, which won three races in 1985 and two more in 1986, while basically the other engine manufacturers followed Renault's introduction of small volume turbo engines.

It was really only a regulation change that started the outlawing of turbo engines at the end of 1986 that brought it all to a halt. Renault then took two years off whilst focusing on designing and developing a V10 package.

When it came back in 1989 it was Williams that had most of the success with Renault V10s. In 1989 it won two races, in 1990, there were two more wins and in 1991, the real success started with seven wins. The 1992-94 Williams, 1995 Benetton and 1996/97 Williams were constructors' champion cars with Renault power, so it was six world championships in succession as an engine manufacturer.

Renault then took another break from 1998 and in 2001 came back with a wide-angle 110-degree V10. The concept was about lowering the centre of gravity of the complete package, but it didn’t give the advantages Renault expected and it was abandoned in favour of a 72-degree V10 for 2004/05 - Renault winning the championship as a constructor for the last year of the V10 era in 2005.

For 2006 the regulation changed to outlaw V10s, which meant Renault had to design a V8, and again it won the championship as a constructor (for the final time) in 2006, the first year of those regulations.

During that period it teamed up with Red Bull and supplied it with constructors' championship-winning engines for 2010 through 2013. Then again for 2014 the regulations changed to what we currently have with the V6 turbo hybrid units.

Considering its earlier success with turbo power units, Renault and everyone else expected it to be a force to be reckoned with. However, the times and personnel had changed dramatically since the late 1970s and early 1980s and Renault has never really come to terms with this package. Part of the problem was having never invested the time and resources needed like engine-era benchmark Mercedes had.

Renault still won three races in 2014 with Red Bull and then nine more before Red Bull left for Honda for 2019. Renault power has scooped just one win since then (Hungary 2021 as Alpine) and during that period, both reliability and out-and-out performance just weren’t there. It's believed Renault could be 20 to 40 bhp down on its engine rivals.

So, after all its innovation in the early days, 770 grands prix, 213 poles, 169 wins and 12 constructors’ titles as a team or power unit supplier, Renault is saying au revoir as a power unit manufacturer to F1.

Alpine will use Mercedes power units going forward. In reality do we really know which engine is in which car when the bodywork is fitted? I wish the FIA would dictate that the engine cover must be removed for the show and tell sessions prior to each race. It would be great to look under the bonnet.

Will Renault’s engine division regroup and be back? It looks unlikely, but who knows, it has effectively pulled out twice before.