Formula 1’s new-for-2026 front wing active aerodynamics, which were a novelty when first spotted in action, have turned into a point of early technical intrigue.

Footage of the Ferrari’s front and rear wings opening and closing, with Lewis Hamilton behind the wheel, spread very quickly during the course of its shakedown at Fiorano in January.

And when 10 of the 11 teams took part in the Barcelona test at the end of the month, looking for brief glimpses of the movable wings in the brief bits of on-track footage released each evening was an F1 tech equivalent of trainspotting.

It revealed something of substance, not just satisfying a minor curiosity: two teams have departed from convention with a key element in their front wing and nose designs that impacts how their active aero works.

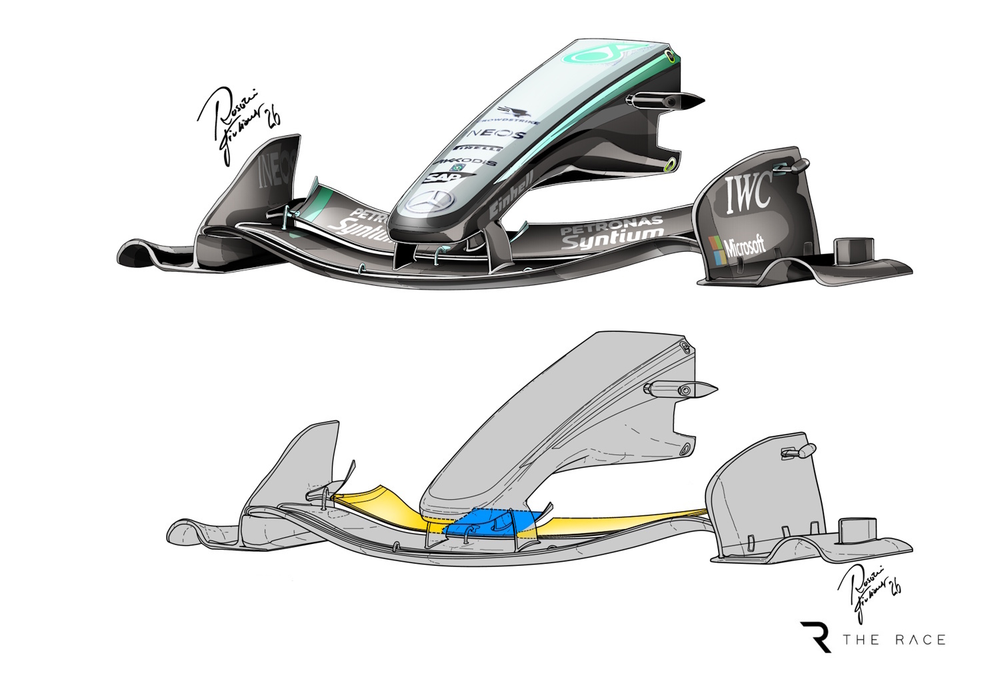

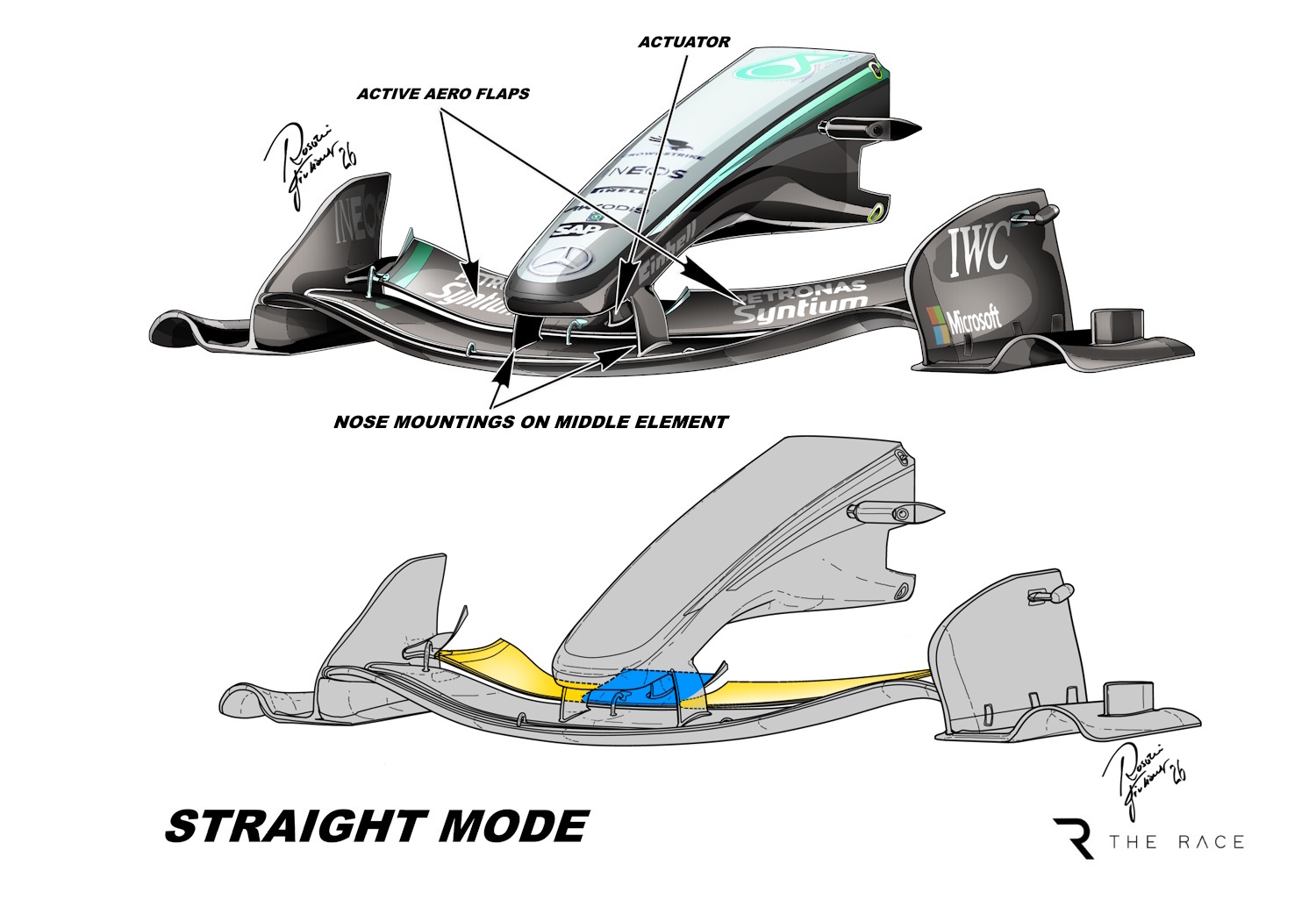

One is Mercedes, tipped very early to be the car to beat this year, and the other is the first Adrian Newey-led Aston Martin design. Both have the nose mounted on the middle of the three front wing elements whereas the most common design is for the pylons to be fixed to the mainplane, as illustrated by Ferrari's below.

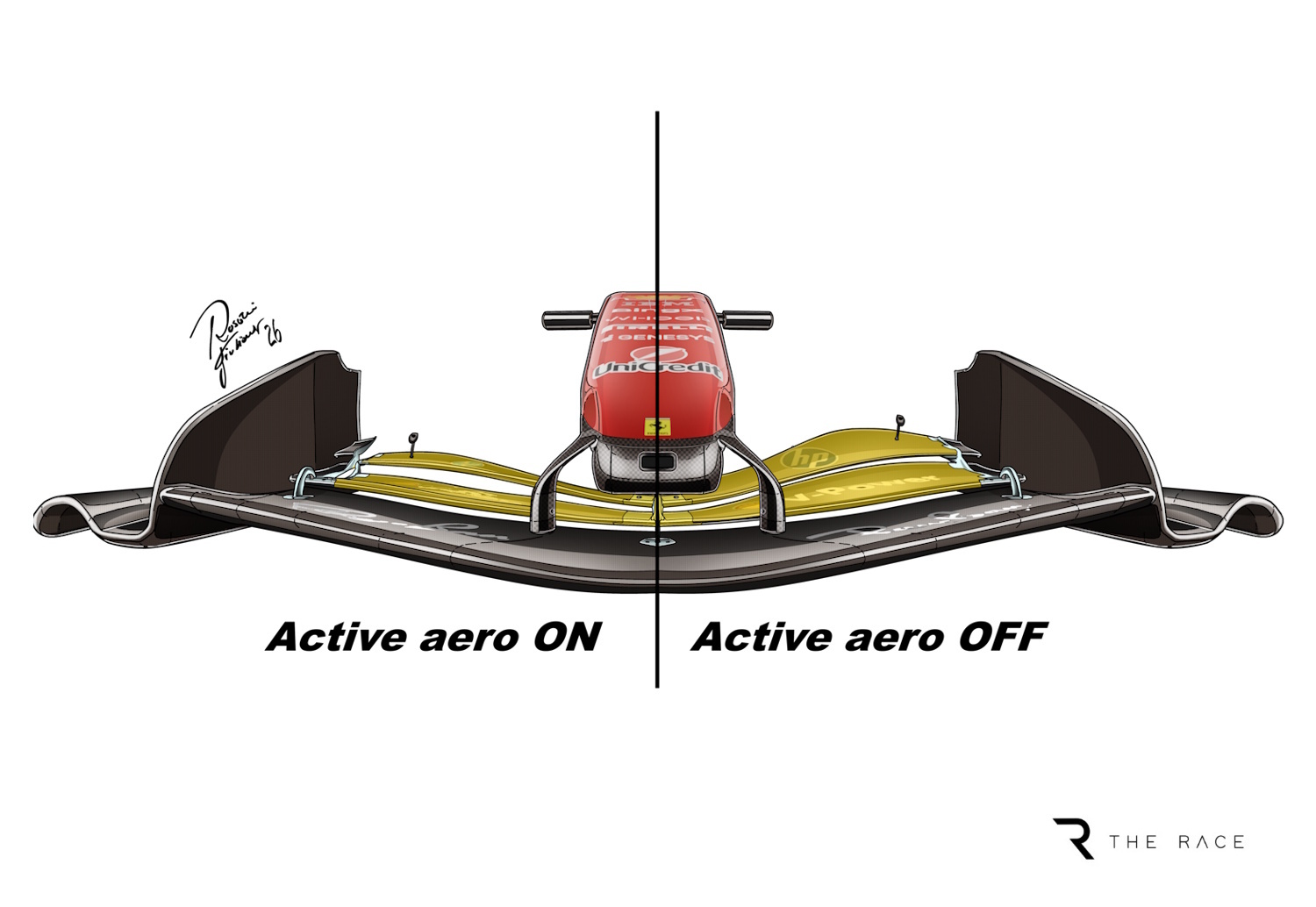

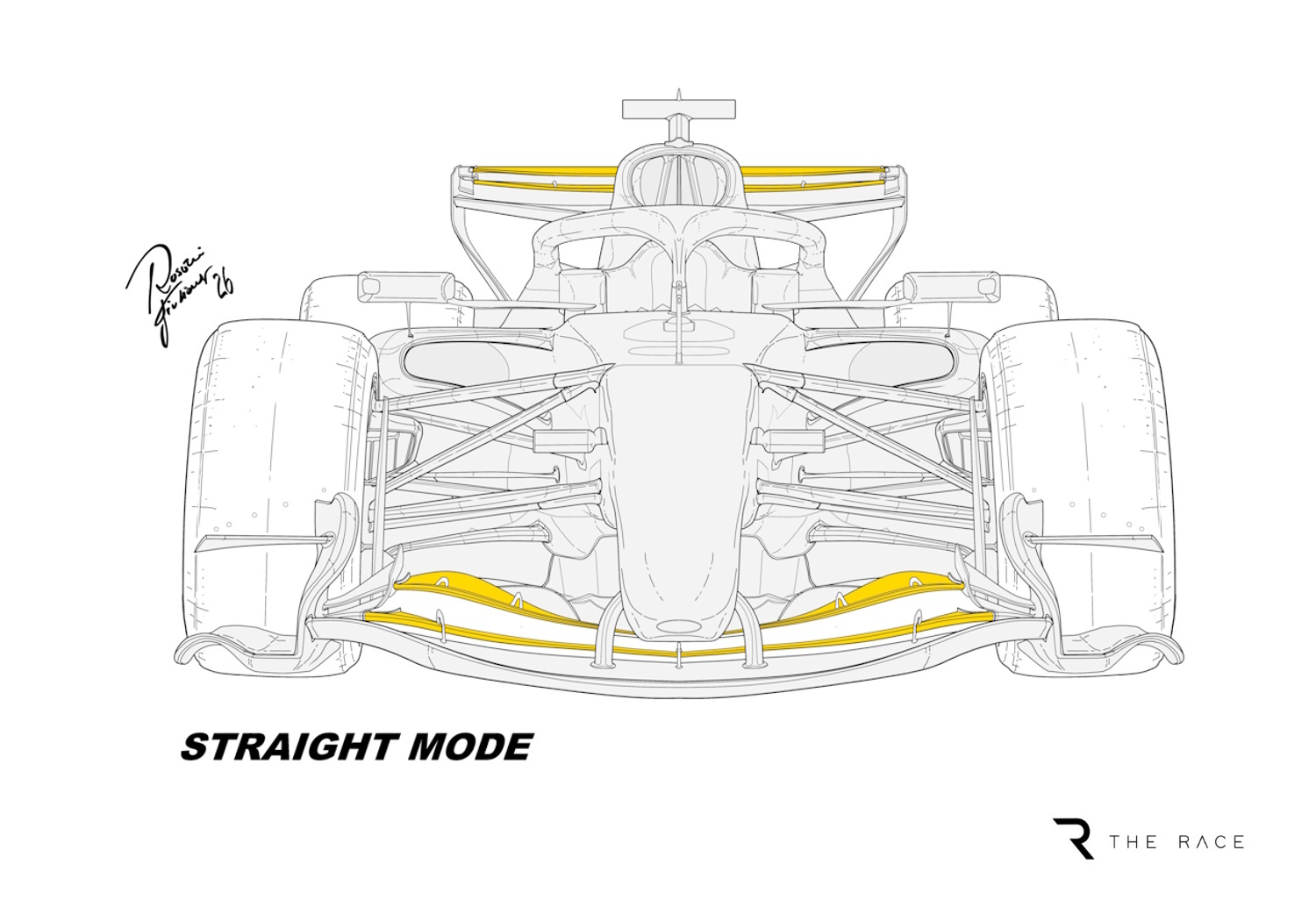

It is no surprise this was the common choice because the rules allow for two front wing elements to change position between straightline mode and cornering mode. And backing off two elements is theoretically better than one to get the maximum drag reduction benefit on the straights.

To enable this, the nose has to be mounted to the mainplane otherwise the middle element is locked in place. Mercedes and Aston Martin have decided to only move the upper-most part of the front wing (illustrated below).

This is the more critical component where active aero is concerned because the angle of the front wing flap is much steeper. Most of the drag reduction will come from the actuator flipping that part of the wing, whereas the middle flap is much shallower and therefore confers a smaller benefit.

Exactly why Mercedes and Aston Martin felt this was the better decision overall is unclear but there are several potential arguments for it.

One is that it allows the tip of the nose to be slightly shorter, and higher, which could allow for more airflow to pass under the car. Given the front wing sets the flow direction for the rest of the car this has to be considered a critical part of its aerodynamic design.

Another reason is how these teams have judged the downforce and drag demands for their cars, and the consequences of how these levels shift with active aero deployed.

If the drag impact is minimal it could be better to have the middle wing element held in place to avoid as much airflow having to reattach when the wing switches back into its normal position for the corners – and it could afford a better balance between front and rear downforce by keeping that little bit of extra wing on the car.

As McLaren driver Oscar Piastri said, the front and rear wings opening together with this active aero makes the car feel a lot more lazy. Usually this won’t matter on completely straight parts of the circuit but as the cars could be in straightline mode through small kinks, for example, it may make the car a little more responsive when needed.

There will also be small - maybe negligible, maybe not - impacts on ride height and tyre temperatures based on how much downforce is shed when the drag comes off so adjusting two elements instead of one could be considered unnecessarily disruptive or deceptively impactful over a race stint or in certain conditions.

It is also a better design structurally. The mid-plane carries the maximum load so supporting the wing is easier to achieve with the nose fixed there.

This will be an interesting area to monitor for development. Front wings are a bolt-on component and typically rife for upgrades across a season but it depends how the physical designs interact with actuation systems and the overall aero concept at the front of the car and how that impacts the rest.

If the nose mounting points (and knock-on effects with active aero) have big downstream influence it will take significant work to be confident that a change in design is worthwhile. But it may also be that teams find huge potential for customisation in set-ups by tuning their active aero differently for different tracks as they strike the best balance between drag reduction on the straights and everything that impacts about the car.

Presumably teams will drop the conventional notion of designing and building ‘families’ of wings - e.g. high, medium and low downforce - and instead will tailor their active aero deployment along those lines. Maybe that means the different structural designs will be a red herring and it will be primarily about how they are used.

By comparison the rear wing continues to function almost universally like the old drag reduction system did - with the rear wing flag popping open.

Alpine has a slightly different design that moves the trailing edge of the wing back, backing the top of the wing off rather than opening it. This means a smaller opening and presumably less of a drag reduction effect, but also the conventional DRS-style separation keeps the flow attached to the two flaps that have been opened up.

As Gary Anderson explained on The Race F1 Podcast, this should allow the rear wing to function at maximum downforce faster and more predictably whereas the wing camber changes with the Alpine design, and the airflow needs to be re-energised.

It is too early to judge which is more effective or even if these turn out to be the designs team race with but for there to be distinctive options at both ends of the car is makes it an interesting technical angle to monitor.