The Hypercar/GTP category that headlines both the World Endurance Championship and IMSA SportsCar Championship is unique in that it blends two technical regulations: LMH (Le Mans Hypercar) and LMDh (Le Mans Daytona 'h', a letter whose meaning has never been officially explained).

However, in recent months, LMDh manufacturers have been calling for a change.

Organisers the ACO and FIA appear to be listening. But how can everyone be satisfied? Should one of the two platforms be banned? Perhaps not, but a convergence between the two is not out of the question. Possibly as early as 2028.

The differences between LMH and LMDh

Initially, the WEC had planned to adopt a single technical regulation: LMH. But as both the WEC and IMSA realised their future relied on unified rules, they resumed discussions and announced in January 2020 that, from 2023, LMH cars would be joined on the WEC grid by cars built to a new regulation called LMDh, with an Equivalence of Technology system put in place.

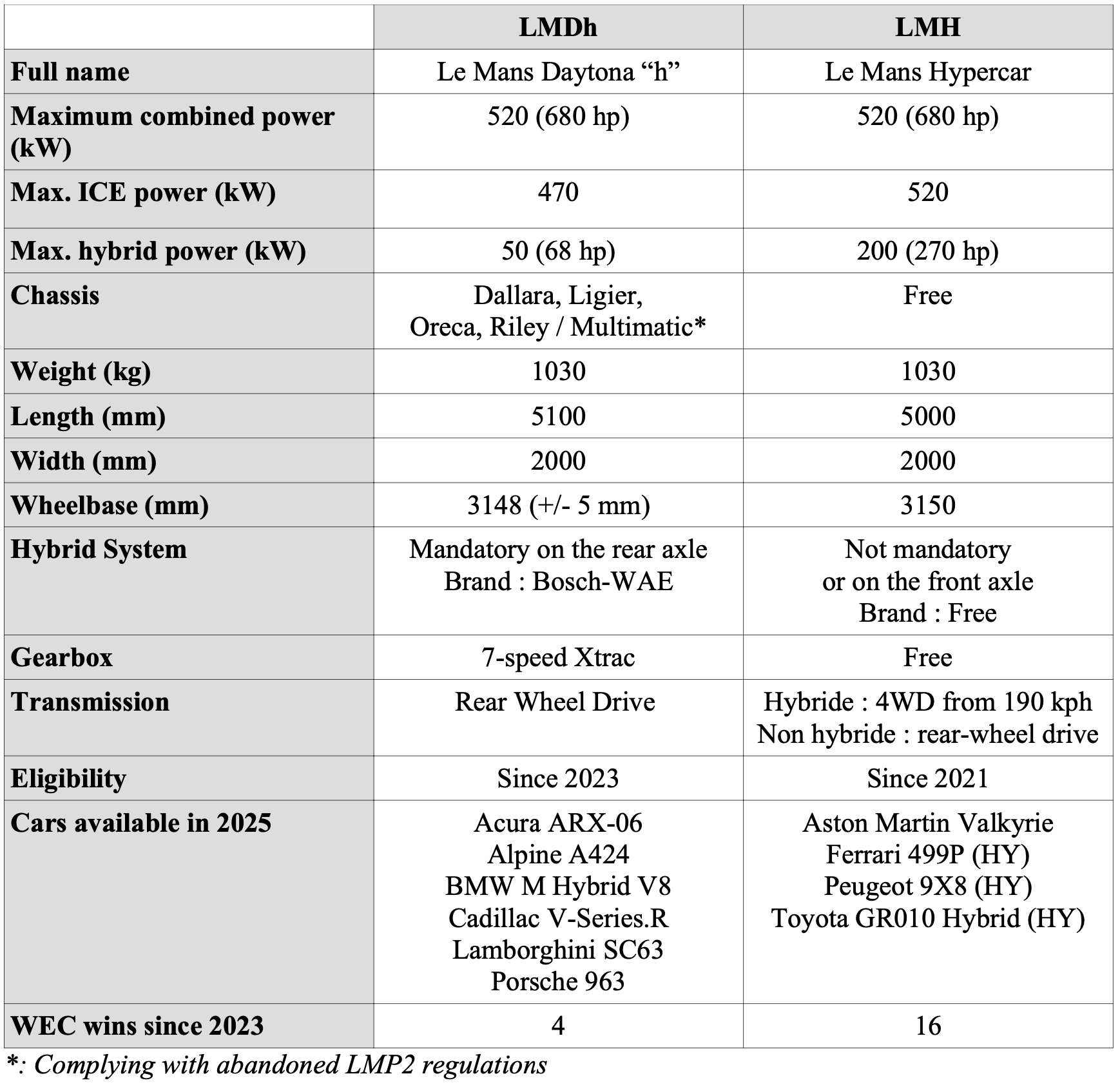

In short, LMH cars are based on a chassis and a hybrid system (optional) both designed in-house. LMDh cars must use a chassis developed by an approved supplier (based on the now-defunct LMP2 rules), a Bosch energy recovery system, a Fortescue (formerly Williams Advanced Engineering) battery, an Xtrac gearbox, and Cosworth electronics. For more technical details, please refer to the chart below.

Manufacturers who opted for LMDh did so for budgetary reasons. Toyota and Ferrari preferred LMH as they wanted to design their cars in-house and showcase their engineering expertises. Peugeot had no choice but to use a Saft battery, a company owned by TotalEnergies, its main partner.

Is this difference problematic?

Ask both camps and you'll get two different answers, each defending their own interests. All-wheel drive kicking in from 190km/h (118mph)? Given the high (and raised, thanks to the convergence) activation speed, it's doubtful this offers a significant advantage.

But according to some opponents, this allows LMH cars to simulate a kind of ABS that gives them an advantage under braking or in tricky conditions, something prohibited by the rules and denied by the teams. "You never see a Ferrari lock up its wheels," joked a driver of an LMDh car. "And just look at how it can overtake others on the outside of a corner, something we simply can't do."

There are also technical differences, such as aero flexibility (with smaller flex tolerances for LMDh) and the floor design, which is freer for LMH. Additionally, if Alpine wants to change anything on its chassis, it needs approval from other manufacturers also using the ORECA chassis, namely Acura, Genesis, and soon Ford. The hybrid systems also differ (see chart above).

On the other hand, some argue that having the hybrid system on the rear axle gives LMDh cars an advantage in power curve management, critical in Hypercar/GTP. Additionally, LMH manufacturers must manage the extra weight and reliability issues from the additional drivetrain.

There are pros and cons on both sides. Some are calling for convergence, while others believe the Balance of Performance (BoP) is enough to smooth out these differences.

Still, even if the Equivalence of Technology was removed from the BoP before the 2024 Le Mans 24 Hours, the ACO and FIA admitted to switching to a new BoP system last winter to address the supposed advantage of LMH over LMDh.

How can convergence be achieved?

Since 2023, LMDh manufacturers have felt disadvantaged compared to LMH teams. Recently, they've started voicing their concerns publicly, like Andreas Roos, head of BMW M Motorsport.

"I'm clearly in favour of a single technical regulation and that we don't have LMH and LMDh anymore," he said. "Le Mans has shown this once again. We are trying to have a level playing field, but because of the technical regulations, it is sometimes a bit difficult, and I think that to reach the next stage of convergence, it would be good to have a single technical regulation in the long term."

"What's certain is that it would make things easier for the rulemakers," added Alpine vice president of motorsport Bruno Famin at the São Paulo 6 Hours recently.

The most outspoken, however, was Thomas Laudenbach, Porsche Motorsport vice president, when he addressed the press in February during the Qatar 1812km.

"The first and most important thing is to get rid of these two different sets of rules, so that we're not going to talk about LMH and LMDh anymore," he explained. "No matter how you would call it, and no matter what it would look like. Without being very precise, maybe it's some kind of mixture between LMH and LMDh.

"I'm not saying we carry over LMDh rules for everybody. But let's put these two sets of rules side by side and let's talk to the manufacturers about what is important for each of them."

If their request is granted, it could mean banning all-wheel drive, applying stricter rules for LMH hybrid systems and underfloors, or removing the requirement for LMDh cars to use one of four pre-approved chassis, or at least allowing more customisation.

When will the regulations change?

Originally, 2030 was discussed. But now, paddock talk hints at 2028. Really? To clarify, The Race spoke with ACO President Pierre Fillon at Interlagos earlier this month.

First, we asked why the decision was made to extend the current regulations through 2032.

"The trigger was the arrival of new manufacturers," he explained. "Ford and McLaren are joining in 2027. It's hard to tell them their cars will only be eligible for two seasons.

"We also wanted to offer competitors visibility and stability. There are things to improve, but the championship is working well. However, the terms of this extension still need to be discussed with the manufacturers. Should we improve convergence, for instance? That's one of the questions we need to answer before the end of the year."

When we raised the challenge of creating a single platform, Fillon replied: "It's not impossible."

But by 2028?

"It won't be before 2027, that's for sure," he added. "Will it be before 2029? The discussion is open. But we're not looking to force everyone to build a new car and explode the costs.

"We need to work on improving convergence and reducing the technical gap as much as possible. Though I think there's a bit of fantasising involved too. The fact is that LMH cars have won more than LMDh since the championship began. Is that purely down to the technical platform? I can't say for sure."

What do LMH manufacturers think?

Such a change would require current LMH manufacturers to design new cars, not something they had planned. Ferrari wants to build its own chassis, Toyota insists on having its own hybrid system, and Peugeot must use a Saft battery.

Peugeot faces another challenge: as The Race revealed, it is working on a new car it hopes to debut in 2027. A rule change could force it to keep racing its underwhelming 9X8 for two more seasons.

"For us, the key has always been the hybrid system, not all-wheel drive," admitted Peugeot Sport technical director Olivier Jansonnie.

"But also the ability to fully control the car's design to bring our technology to racing. If the rules were to change and impose two-wheel drive, but we could still control the design, that would be OK for us. We've actually been pushing in that direction."

And Toyota?

"We believe there's a higher priority to work on [BoP]," an annoyed Kazuki Nakajima told The Race. "I think there's something more important to act on in the short term than discussing whether to build a new car or not. That's our position.

"For the longer-term future, we're open to discussions to create a fairer playing field. It's hard to make things fair in competition, but we're willing to work together. As for 2028, we're not really involved in that conversation yet, but we'd like to be."

"It's clear we need to build our own car and develop technology through racing," he added. "And we're also keen to explore hydrogen. I can't say we're committed, but we're eager to work on it, and timing is crucial. These things must be discussed carefully."

Yes, because in the coming years (if this is possible by 2028, the first cars are not expected to arrive before 2030) an additional hydrogen-based technical platform will appear, necessitating the implementation of an Equivalence of Technology system.

"We have to anticipate all of this and think long-term," added Toyota Gazoo Racing technical director David Floury. "It would be wise to start thinking now about how hydrogen will be integrated into the category."

2028 seems a bit premature. It would require manufacturers to start development immediately, something not necessarily accounted for in their business plans. But the future of some programmes, including Porsche's, may depend on technical convergence.

"One thing's for sure: we'll need to have answered these questions by the end of the year," said Fillon.

Keeping everyone happy will not be an easy task.