Alpine's impending replacement of Jack Doohan with Franco Colapinto may feel preordained given the prospect of it has been a shadow over Doohan throughout his seemingly shortlived Formula 1 career.

While still unofficial, Alpine's intention to put Colapinto in the car in Doohan's place from the next F1 race at Imola fulfils an expectation many have had since the 2024 Williams stand-in joined Alpine on a multi-year deal in January.

That move put Doohan's place immediately at risk. But as likely as a change seemed this season, it was never guaranteed. The sands shifted more than once and until very recently a swap was not certain at all.

Commercial implications have been at play since Colapinto came onto Alpine executive advisor Flavio Briatore's radar last year, and even when Doohan seemed to get the all-clear until the summer there was a school of thought that it was really just an attempt to flush out more backing from Latin America.

But it would do Colapinto a disservice - and be a naive assessment of Doohan's start to 2025 - to pretend there is no competitive element to this at all. Colapinto represents no obvious downgrade based on Doohan's failure to quickly build on the good underlying pace he showed early in the year.

At worst, Colapinto may be a crash risk, and may not be a superstar in the making - the sample set of a part-season at Williams is too small to know for sure on both counts - but he is a proven point scorer already and is a driver with ability.

Want more on why Alpine is dropping Doohan? Hear from the man who broke the story, Scott Mitchell-Malm, in The Race Members' Club on Patreon. Head to this post and sign up now, 75% off your first month!

Still, the obvious question is why this had to happen now, just six races into Alpine's own academy graduate's rookie season, given it is a decision not universally believed as right within Alpine.

The simple answer is a mix of factors: that this is what Briatore wants, that it seems some more funding is arriving at Alpine from Latin America in some way or another, and that Doohan was unable to produce an early body of work to offset those two things.

That all makes it feel somewhat inevitable. Partly because it's been a months-long saga always trending in this direction, and partly because of how the last few weeks have gone.

The situation has had an underlying tension attached to it from the very beginning and it always seemed unsustainable for Doohan trying to thrive in a compromised environment, and for the team immediately around him trying to work with (and justify) an arrangement ultimately created by someone else.

This ultimately manifested in an impact on what might be best broadly termed Doohan's 'relationship' with the team, and subsequently his performance and well-being.

The Doohan/Alpine dynamic did seem to subtly shift over the six race weekends. Although that should not be taken for a suggestion that Doohan suddenly became unpopular or disliked - it is understood that the opposite is the case, and Doohan retained support from a lot of people in Alpine.

But - sometimes publicly, sometimes a little more privately - the unequivocal support many in the team genuinely wanted to give him started to waver at least slightly, and things grew at least a little frayed. Mainly because Doohan started to exhibit the first signs of a driver feeling like he was losing his own team's backing.

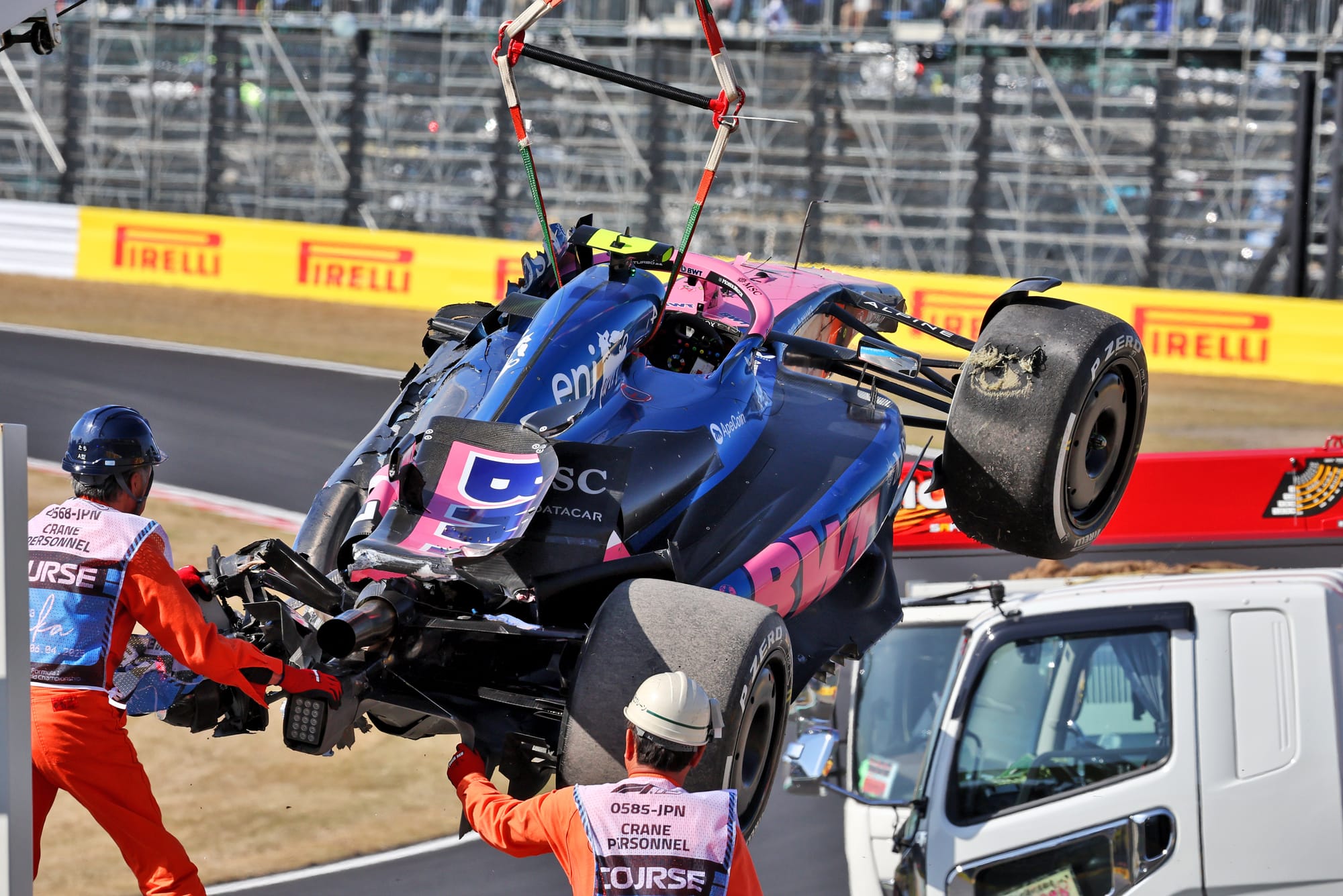

He was not happy with how Alpine handled his FP2 crash at Suzuka, believing he should have been supported more for the DRS error that triggered his high-speed shunt. It was Doohan's mistake not to close the DRS but, having only done the same thing he did in the simulator and not been explicitly told at any point to do anything different, he was known to feel that there was a degree of responsibility on the team's side.

There were plenty high up in Alpine that were trying to help Doohan as best they could in reaction to that crash. But he, to all intents and purposes, took the blame. And Doohan never seemed completely placated by Alpine's reasons for that. It was, at least to him, potentially the first sign that he would not be afforded the full extent of the protection he felt he deserved.

That is a familiar sentiment among drivers who know they are vulnerable, and it leads to the second consequence: the impact on the driver themselves.

Doohan's impossible position meant he went into not just his rookie season but his very first race weekend last year in Abu Dhabi with question marks about his future and the pressure he was under.

And initially, Doohan handled this superbly - he navigated a thorny situation well, got a little punchy when he needed to, to the point where Alpine's semi-regular interventions to shut down certain lines of questioning probably weren't necessary as he usually handled it well himself, and generally left a good impression.

Doohan didn't seem unsettled, he seemed determined. And he channelled it into an encouraging start, recovering from a tricky Bahrain testing with a minor mechanical set-up tweak that brought more out of him. But he didn't translate the promise into results quickly enough and the list of setbacks is quite substantial for six events: lap one crash in Australia, penalties in the China sprint and grand prix, practice crash in Japan, a late fall out of the points in Bahrain, and finally the first corner collision in Miami.

And all the while the noise - which team boss Oliver Oakes admitted Alpine had created in the first place - continued. So, the longer this went on, and as it became accompanied by difficult results, and that potential perception that he was more on his own than he thought, Doohan started to react a little more emotionally.

That's no judgement, just an observation. He got more combative in media sessions, was more vocally critical of his team over the radio (Miami sprint qualifying being the ultimate example) and just seemed to grow a little exasperated with the scrutiny.

Few would have appreciated the Netflix cameras and microphones descending on them in the manner they did Doohan after the sprint qualifying session in Miami - capturing him returning to Alpine hospitality upset and frustrated, and then be on the receiving end of a telling-off from his team boss for the manner of his radio messages.

In Doohan's defence, that's a hard set of circumstances for an athlete to be at their best in. But Briatore didn't seem to buy the argument that it was unnecessary pressure, or unusually difficult. Hence fostering a situation that made it so awkward for Doohan and for those on his side.

It's also possible that the worse Doohan reacted to it, the more it became a self-fulfilling prophecy. F1 never really saw the best of Doohan in these first six weekends - even though there were glimpses of good speed and a strong approach - and was less and less likely to the longer this went on.

It didn't help Doohan on-track, and how he was handling the trickiest moments perhaps even eroded some of the patience those on his side within Alpine had, too.

Plus, the job done by other rookies in the midfield - Ollie Bearman last season, Isack Hadjar this, just to name two - left the impression that while six races was a tiny sample set, it was enough to see if Doohan 'had it'. And Briatore doesn't think that's the case.

With the threat of a change always there, and witnessing how much harder it seemed to be getting for him, the situation sadly never looked like swinging back in Doohan's favour.

If anything, it became unworkable. Hence an inevitable change, and such an unsatisfying end for Doohan and the people who stood in his corner.