This could be Singapore. Or anywhere.

If you'll pardon the slightly tortured, tangential Beautiful South reference, the environmental chamber at the University of Roehampton is our gateway to 'anywhere' - in this case the streets of Singapore and the hot, humid conditions Formula 1 drivers are grappling with this weekend.

And I am the guinea pig - so ascribed by environmental physiologist Dr Chris Tyler, who's overseeing this experience - lucky or unfortunate enough (depending on your outlook) to be experiencing those conditions in an active setting to get a feel for the demands that environment will place on the drivers.

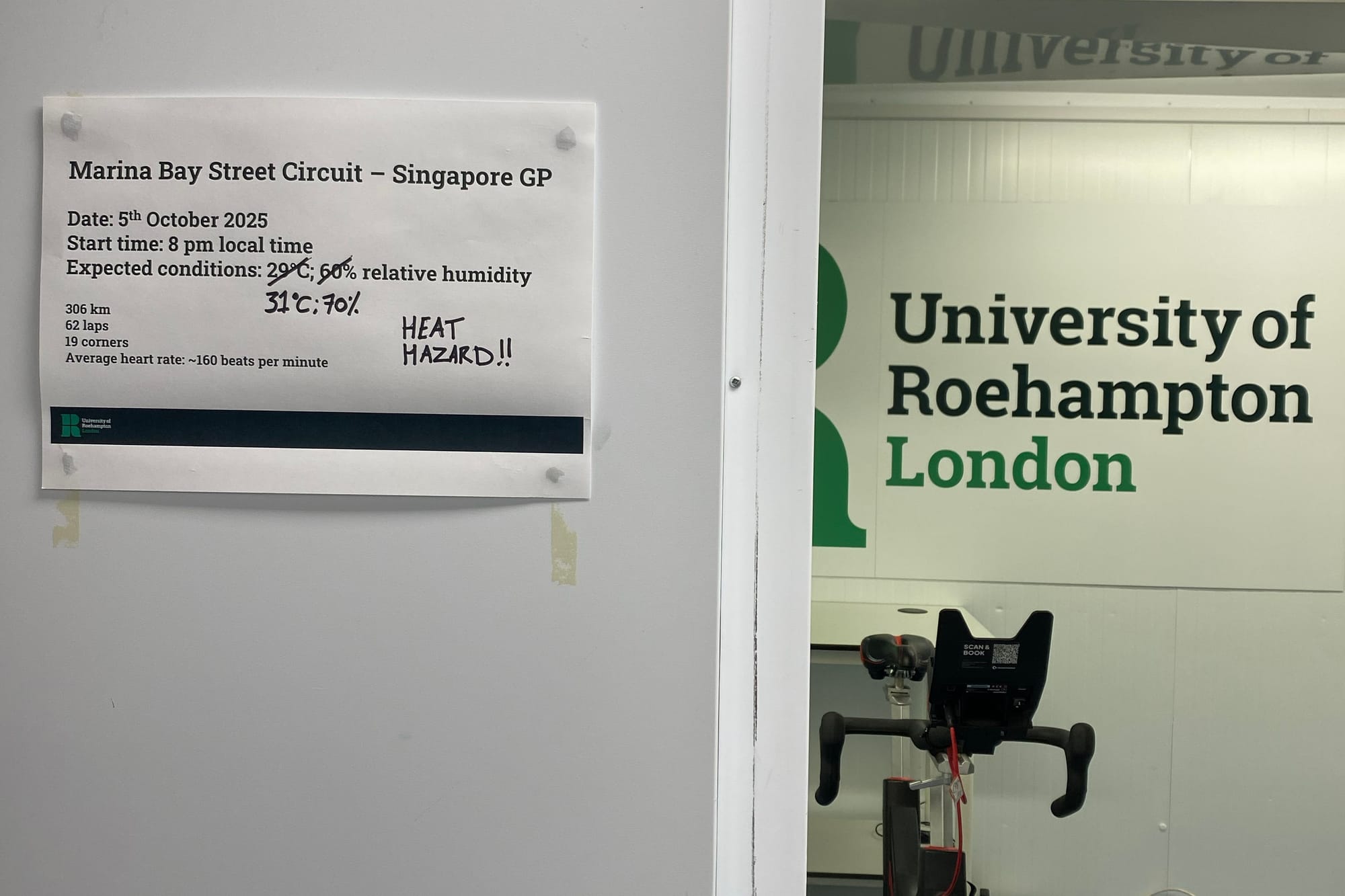

It's a timely opportunity, too, considering this weekend's race at the Marina Bay circuit is the first in F1 where a 'heat hazard' has been declared.

The set-up

We're in a state-of-the-art facility, unassumingly tucked away at the University's Whitelands College in South West London and used by the likes of Oscar Piastri and Carlos Sainz but also the UK's fire services to train to cope best with extreme thermal strains.

We're here - I'm accompanied by Samarth Kanal - to get as close a feel for the conditions at the Marina Bay circuit as possible, so after an initial tour of the chamber it's time to prepare for the simulation: a 45-minute workout on a wattbike, in which the aim of the game is to get to around 160bpm - roughly the heart rate you'd expect an F1 driver to have during a grand prix - and stay there.

For the full experience, we've agreed to a few extra measurements. Starting (and ending) mass is taken and, in addition to the heart rate monitor and four skin thermistors that will measure my skin temperature, I also insert a rectal thermistor so the change in my core body temperature can be charted throughout.

The room is set to an air temperature of 31°C (the temperature threshold beyond which a 'heat hazard' race can be declared in F1) and 70% humidity, a 2°C and 10% increase on the forecast a week earlier.

Those might sound like small increases, but it's the humidity that makes the big difference: the greater the humidity, the less liquid can evaporate. Plus, as I prepare to cook in the race suit I've stepped into, the air temperature isn't much of a consideration for me, even less so for actual F1 drivers - as they're not in contact with the air.

Suited, sensored up, and in the saddle. Ready for another normal Friday.

The experience

We've chosen 45 minutes for the workout to simulate close to a half a grand prix's worth of time on the bike. (Though the Singapore GP tends to be the longest on the F1 calendar; the 2024 edition was the shortest in the race's history and even that ran to an hour and 40 minutes, so we're cheating slightly.)

While my physical fitness was never going to compare to that of the likes of Piastri or Sainz, it's at this point that two excuses are getting thrown in: I am slightly under the weather and nursing a running-related injury (hence opting for the bike instead of the treadmill).

Still, a 160bpm workout falls into my 'zone 3' exercise range - so it's not necessarily physically exerting as I begin to build up to that level. Four minutes in and the first beads of sweat start to form and fall away, but conversations are no trouble at this point.

Just like those experiences out on a kart track where your talent shortfall is quickly exposed, it's not long before the athletic reality starts to hit home. There's a first real complaint, of some brain "fuzziness", as the 20-minute mark passes by - 12 laps into the race, according to my increasingly clouded calculations - and the admission that doing five times that much is already unimaginable, as the sweat creases in the fabric stitches of the suit start to expand.

At this point, while I'm still climbing towards the average heart rate target, the physical impact doesn't feel so strong; it's the mental fatigue that's starting to set in earlier.

That's no reason to be fooled, either. Those bodily reactions are on a bit of a delay as the heat starts to get trapped in the overalls - almost every bit of heat I produce or gain isn't going anywhere - and it's not until a little while after the session that my core temperature will actually peak.

And the catch-up point feels like a bit of a sledgehammer to the body: it's inside the final 10 minutes of the session, well after I've got to 160bpm, but from then on it's a slog as the humidity becomes increasingly invasive and my face fills with colour. Every glance away from the clock is an attempt to fixate on something else and distract the mind, only for my eyes to return to the screen and see barely 15 seconds have elapsed!

But the end is in sight. My left index finger goes up with a minute left on the clock and 60 seconds later is replaced by an OK signal to signify I'm done. It's a cautious dismount from the bike as I feel a degree of light-headedness at this point, and a moment before I'm steady enough to have the sensors removed. Is it any wonder we've seen drivers hunched over hoardings - in some cases requiring medical assistance - at the end of races such as the 2023 Qatar GP?

The results

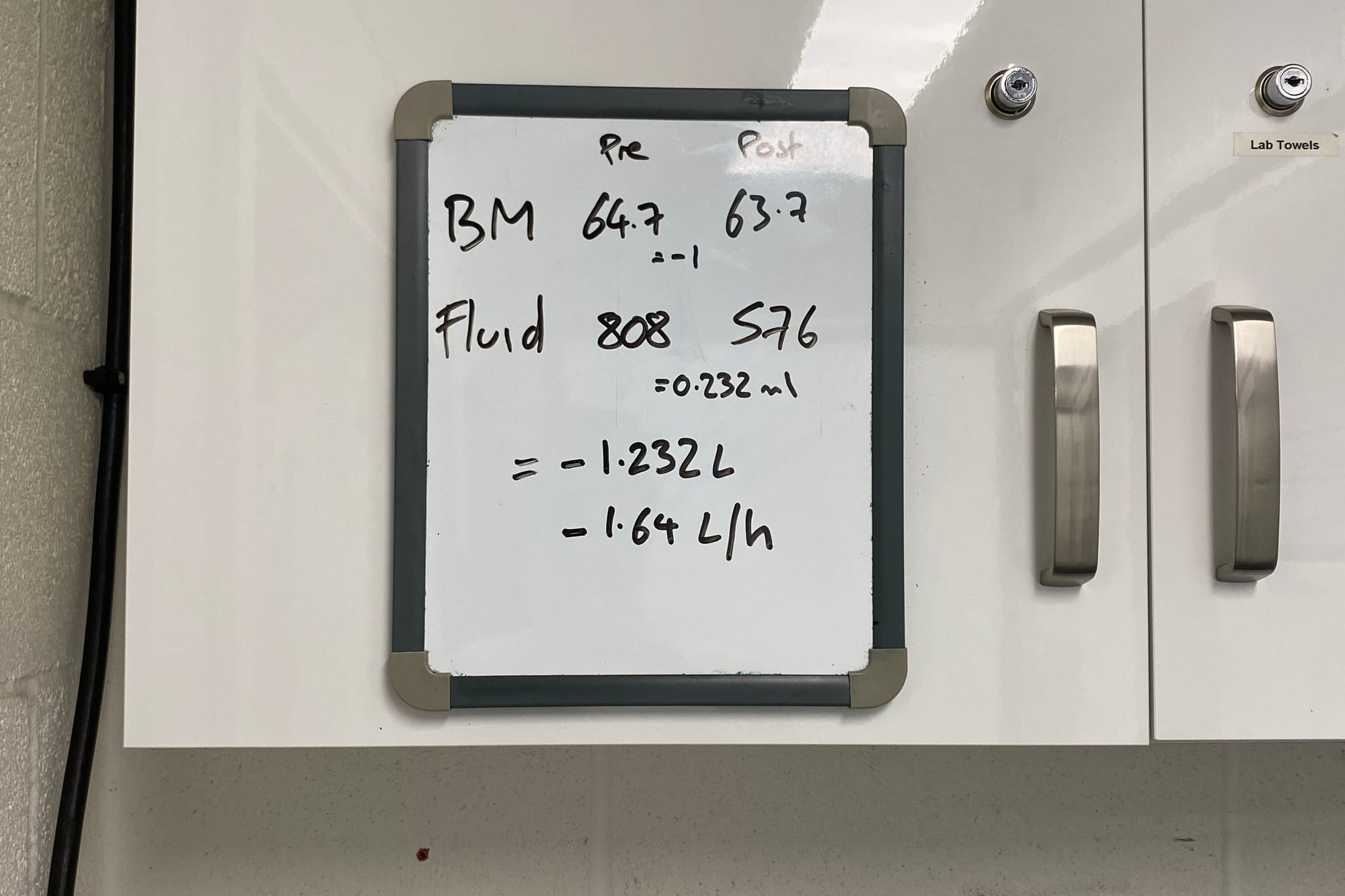

In the space of just that 45-minute session, I lost 1.232 litres of fluid, and a full 1kg both literally and metaphorically drained from the body.

That was a little more than 1.5% of my starting mass which, while the progress wouldn't be linear, would fall in the range of 2-3% body mass lost over the course of a grand prix - in the ballpark for a grand prix driver, too.

My core temperature increased by around 1.4°C, too, to 38.9°C. Though the data on F1 drivers' temperatures is limited, Dr Chris says this is in the range of what you'd expect an Australian Supercars' driver's to be, as that core temperature is dictated, to a degree, by the exercise intensity.

The takeaways

Wow, that was unpleasant!

To deliberately butcher the common phrase, this wasn't an exact science. I wasn't in a cockpit, and I wasn't wearing a balaclava, helmet, HANS device or gloves - a double-whammy of added downsides as that would've meant I was carrying extra weight and would've prevented any heat from escaping.

But it was still a fascinating insight (once I'd regained my composure) into what the drivers will be going through in Singapore.

Most of you will have been to humid places and felt the accompanying heat, too. But having now had some indication of even half the level of exhaustion they'll experience I can comfortably say there is no way to accurately comprehend it just on assumption.

And it's a mental challenge, too. Those final minutes of clock watching didn't make for a particularly nice headspace to be in.

Even looking at it with my media hat on, this was an enlightening experience. As someone with some degree of sporting ability and a sometimes-stifling competitive nature, I've never been a particularly good loser and can from time-to-time have the temperament that you'd expect to match that particular character flaw.

I actually like to think as a result I'm a bit more tolerant of the flashes of petulance you might see or hear from drivers. But when you take the kind of competitive drive these elite athletes have, imagine you double (almost triple) the exhaustion I experienced, couple it with an incident - let's say it's a slow pitstop, or a clash with another driver - and then ask them to get straight out of the car and then come to speak to the media; to me it's remarkable that they manage to be as level-headed as they tend to be.

So, if you ever find yourself wondering, 'How hard can it really be?'...well, hopefully there's some indication.