Patrick Coorey was a young engineer still making his way in racing with the Super Nova team just a few years after coming over from his native Australia. He’d worked with some good drivers – Mike Conway, Tiago Monteiro, Adam Carroll, and Jose-Maria Lopez to name but a few.

In December 2009 he was at Super Nova’s East Anglian headquarters preparing for the new GP2 season where he would be engineering Czech driver Josef Kral, when the phone rang. It was Ron Meadows, the team manager at the then new-look Mercedes F1 team. He had an intriguing request.

Meadows explained that one of its new drivers needed to get some time in a GP2 car to help with race fitness after some time away from racing. That driver was Michael Schumacher.

“I do remember being sat in the office with our team manager and getting that call,” Coorey tells The Race.

“Us testing Schumacher came up because we were the junior team to Brawn, which of course then became Mercedes, and we had a bit of an association with the Brackley team.

“When I heard it was going to happen, I was like ‘oh, wow, that sounds awesome’. It sounded like a brilliant thing to do. But weirdly, no one wanted to actually engineer him, so I put my hand up straight away, like a little reflex going off.

As soon as Coorey did that, the reality and the daunting nature of what he was going to do really started to kick in.

“There was some apprehension because this was one of the greatest drivers ever to set foot in a car,” says Coorey (below), now the team manager of the Jaguar TCS Racing Formula E team.

“But how many opportunities like this do you get in a career? I had to do it, but if I said it wasn’t daunting, I wouldn’t be telling the truth."

GP2 (now Formula 2), through series co-ordinator Bruno Michel and tech lead Didier Perrin, was heavily involved from an early stage, essentially to keep control of the test because they quickly realised that “other teams wouldn't like this happening” according to Coorey.

That was a significant understatement.

The controversy

All competitors in GP2 at the time were supposed to have exactly the same amount of testing with the same number of tyres. Equity and parity were watchwords in GP2.

But this was clearly outside the remit of a normal test, yet it still brought sizeable contention among other teams who were clearly concerned that Super Nova would also use it to advance their own competitive edge for 2010, in which would run Luca Filippi and Marcus Ericsson in addition to Kral.

With GP2 not having a ‘pool’ test car, Super Nova was pinpointed via its link to the newly-defunct Brawn F1 Team. But other teams were far from impressed that Super Nova would be involved.

According to Coorey, F2 tech chief Perrin was asked whether he wanted to engineer Schumacher for equality, but declined. So, it was Coorey who got the job of working directly with the seven-time F1 world champion, whose last Grand Prix was at the 2006 Brazilian Grand Prix, three and a half years before.

Since then, Schumacher had continued to work for Ferrari, often attending Grands Prix and had initially been considered to replace the injured Felipe Massa after his bizarre Hungarian Grand Prix incident in August 2009.

He even tested for Ferrari at Mugello but had significant discomfort in his neck, a legacy of injuries sustained in a motorcycle crash at a Cartegena trackday the previous February.

But five months on and Schumacher was preparing for a return to F1 with Mercedes, and he needed to test out his body again, as well as getting laps in prior to the first-ever 21st century Mercedes F1 car that he would be driving alongside Nico Rosberg.

But the GP2 test had a real race against time frisson to, and for several reasons. The primary one of which was getting a Frankenstein GP2 car up and running in just a matter of days.

“We had to prepare our car because GP2 wouldn't let us run in its normal set-up,” remembers Coorey.

“We had to build their chassis onto our rear end because their (GP2) rear end wasn't up to spec and wasn't runnable. So, for equality and all that, they didn't want us to run our entire car in an extra test that other GP2 teams couldn't come to. So, there was a lot of work for us to do."

Coorey and his colleagues at Super Nova had to build the car and then it had to be liveried up to generic GP2 colours. On top of that, there were a lot of meetings at Mercedes in Brackley.

“I’d go over there, and the main person of contact was engineer Andrew Shovlin (top left, above). I remember going over to do the seat fit with ‘Shov’ and Michael where I met him for the first time. He was wearing his old Ferrari overalls for the seat fit, which was a bit surreal to be honest.

“There was great interest obviously but in a sense it was all quite chilled too considering we were up against it time-wise. Ross Brawn took an active interest in the seat fitting, so it was all quite a close circle of people involved.

“Michael wanted to run in a fast car that he could get some high g-force experience in and see if his neck was okay. That was the gist of it. And for that purpose, we would run with extra downforce for the whole test, almost the whole test, so that the cornering speeds would be up, and we could get it a bit closer to an F1 car performance-wise.”

As the test, which was to be held at Jerez, neared, Coorey and the Super Nova team honed their composite car in the early new year to ensure they could hit the ground running over the planned three day running.

The three-day test

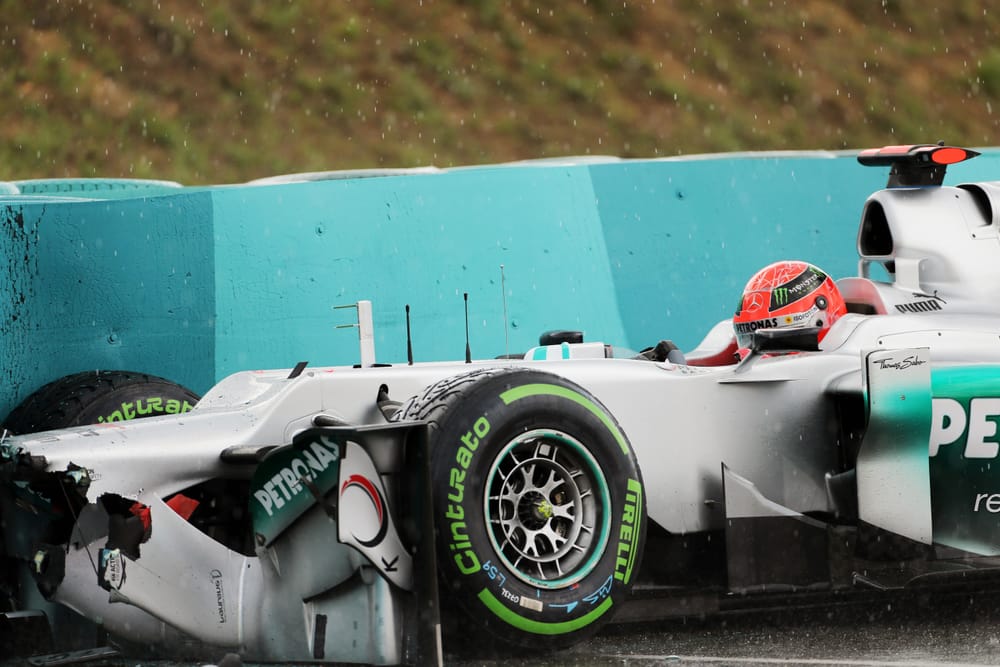

With the Jerez track to themselves, Coorey, Schumacher and the team were disappointed to find inclement weather initially delaying the running.

But Schumacher, whose only prior running in a equivalent to GP2 was in 1991 when he finished second in a Japanese F3000 encounter at Sugo, where he ran in a Team Le Mans-entered Ralt RT23, was soon getting up to speed.

That he had copious amounts of tyres at his disposal was certainly some help.

“I remember being on a phone call with Ron Meadows and he was saying ‘how many tyres can we get?’ and I said ‘normally we have two sets a day. He said ‘no, no, why don’t we have 10 sets a day?’ And I'm thinking ‘that's a bit over the top.’

For Coorey, who was used to a more frugal way of going racing he clearly recalls Mercedes not caring about the cost at all.

“They just wanted to get Michael as much running as they possibly could,” says Coorey.

“In the end, it turned out to be wet almost the whole time. It was wet day one, day two, and day three morning. It only dried up for the final afternoon.”

Because of the fuel capacity of the GP2 car, any Grand Prix race distance had to be done in installments with runs of “around 25 laps” according to Coorey.

It was here, where Schumacher tested out his stamina and consistency, that Coorey became very aware that he was working with one of the all-time greats.

“He was so professional, you wouldn’t believe,” remembers Coorey.

“In GP2 we're used to running drivers that are coming up through the ranks, and they pass through. You don't get them for a very long time, and you only run a driver for one season and they're young, they're learning.

“Michael was coming from the other direction and one thing that struck me was his sheer depth of knowledge. He knew everything. If I wanted to have a technical conversation about dampers or diff or anything, he just knew it inside and out.

“It was to a level that usually only engineers know. Drivers don't usually get that much into it, but he knew everything, really technically proficient. I was really impressed because he was so interested in it.”

'He was like a surgeon'

That aptitude matched with his innate ability inevitably brought a bit of eventual frustration with the GP2 car beneath him, particularly with the limitations on the differential.

“Because we had a mechanical diff with ramps and clutch pack, and he liked the hydraulic F1 diff that he could programme infinitely, he got frustrated,” says Coorey.

“He wanted to isolate it for braking and turn-in and that, and we just couldn't do it. He was just so incredibly technical and very, very sensitive, a machine but a machine that could really give engaging feedback.

“I've never met a driver who's as sensitive as he was. It was like he had in-built sensors.”

There was an incident at the Jerez test that highlighted this part of Schumacher’s armoury. That otherworldly natural feeling of a car's grip and power. The almost paranormal and undefined in-built dexterity that is hard to describe unless witnessed.

“In the wet, everything becomes trickier, so the throttle maps has to be perfect,” says Coorey.

“We were talking about the throttle map, and Michael said, ‘it feels like there's a little bit of a bump in the low part of the throttle map, a little inconsistency.’

“So, I looked at the screen and I couldn’t see anything. It was one of those cases where you turn it on an angle and you look down the line, you could see this tiny little bump in the lower part of the throttle map, it was hardly distinguishable to the human eye.

“I was just amazed that he'd picked that up. We flattened it out and we fixed it and we worked on it further to make it better. But I could not believe that he could accurately predict that, like a 0.2% difference or something. It was just incredible.”

Another memorable element of Schumacher’s ability was how he used the steering. In F1 power steering had long since been a feature, but in GP2, there was no such luxury.

At peak loads a high force of input was needed and Schumacher initially felt it was too high and that he was losing all the finesse in steering that was a big part of his style.

“He wanted to be able to position the wheel perfectly and control it really finely,” remembers Coorey.

“He just couldn't do that, so we did some caster changes and that helped a bit. But it said a bit about how he drove the car and the level of accuracy and finesse that he did with his fingertips. He was like a surgeon.”

The fascination with Schumacher the professional was matched by Schumacher the man too.

“I remember thinking in the lead up to driving, he was quite short and abrupt and not very chatty,” says Coorey.

"Once he got in the car and drove it, he was all of a sudden really chatty and smiling and relaxed and comfortable.

“I remember at lunchtime on the first day when he got out, he was just at ease and happy to be back in the race car. It was like an extension of him, not so much physically, although that was partly true, but more the emotional and mental side.

“He was everything you’ve ever heard about him and probably a lot more.”