Formula 1 held its first collective 2026 test of sorts as the 10 current teams stayed behind in Abu Dhabi to run a mule car each and trial next year's tyres on Tuesday.

Pirelli's mule car programme developing the 2026 tyres has been rumbling away in the background all year with 12 two-day sessions across eight circuits before the final day in Abu Dhabi after the season finale.

This one was the most significant, though. It's the first time that all the current teams have been brought together, and that we've been able to see these mule cars ourselves, plus the test was opened up to include some unique designs after teams have followed a strict Pirelli programme the rest of the time.

So here is what we learned from much more than a standard Abu Dhabi race weekend hangover.

The speed of the mule cars

The tyre test is useful to the teams but falls a long way short of how useful it would be to run using the as-yet non-existent 2026 cars.

These are not anything like the real cars that will race next year, simply a best-possible approximation using current-spec machinery.

While Abu Dhabi is not a maximum-downforce track, the change in configuration means significantly reduced downforce levels compared to the grand prix weekend. The laptimes reflected this, with the fastest mule-car time a 1m25.170s set by Mercedes driver Kimi Antonelli.

That's 2.5 seconds slower than the best Mercedes qualifying time from the race weekend, and that was the closest deficit of all 10 teams in the test compared to the race weekend. The average deficit was 3.93 seconds.

Antonelli's lap was not a no-holds barred qualifying simulation, but it is at least roughly in keeping with the ballpark performance loss recently suggested by FIA single-seater director Nikolas Tombazis of in the region of one or two seconds off the current cars.

The value of the mule cars

Laptime is a one-dimensional metric, though. Williams team principal James Vowles says the mule cars are "just too far away" to give a clear read on 2026, with the real work done in the simulator.

That's because aero balance characteristics will not be a fair representation, the ride will be different given the 2026 ride heights will be higher and mechanical characteristics of the suspension changed and the endless tiny details that aggregate to define the performance, feel and behaviour of a car will all be off.

For the drivers, it's also of limited use as while they will learn a little about the tyres within the limitations we've already talked about, they are still using the old power units.

This means that crucial elements of driving the 2026 cars such as managing the energy recovery systems and modifying the driving technique to maximise harvesting potential are off the table.

However, the mule cars are all that F1 teams have for now, and at the very least it gives them some real-world tyre data to assimilate into their models before the first real tests begin at Barcelona at the end of January.

This test is useful for Pirelli in that it allows the tyre behaviour, in particular the lap time delta between compounds - with the target a step of around 0.7 to 0.8 seconds - to be evaluated as well as other behaviours such as overheating or possible graining.

It also gives all the teams the chance to sample the definitive 2026 tyres as part of their preparations for next year.

They could compare the performance of the final product to both their previous experiences over the past 14 months of testing the evolving prototype tyres and how it correlates with the virtual tyre model Pirelli provides them with.

Plus, in the earlier 2026 tyre tests, Pirelli decided the runplans whereas in Abu Dhabi teams had free rein to do what they want, which amplified how much they could learn even further.

Front wing DRS in action

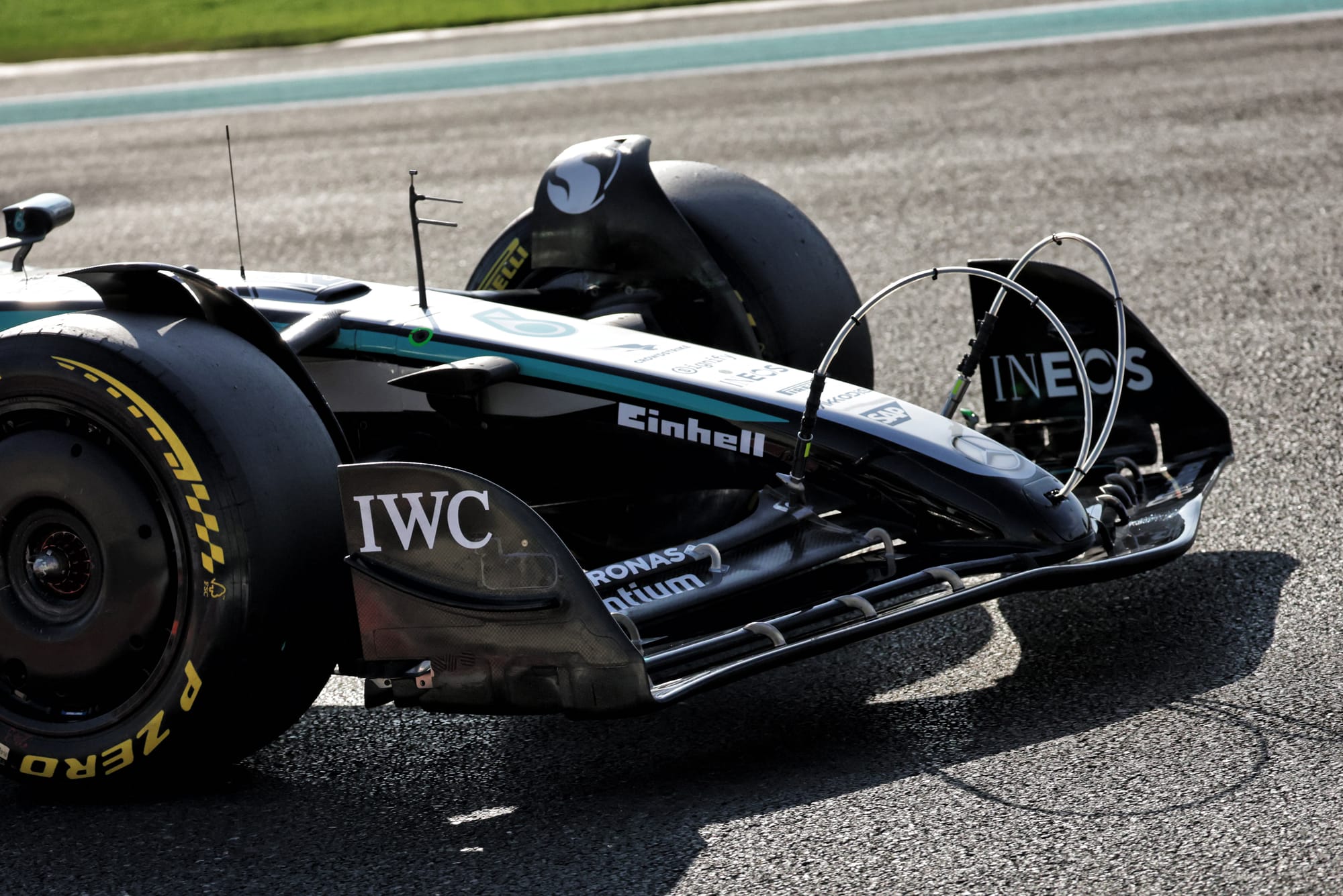

We got our first look at some prototypes simulating the kind of movable front wing system that will be used in F1 next season.

Next year the all-new 2026 cars will feature active aerodynamics on both the front and rear wings to reduce drag on the straights.

That aero profile is being approximated on the mule cars by only using wing levels that were raced at Monza this year, and using the rear wing drag reduction system on more than just the normal long straights that are designated as DRS zones on race weekends.

But in 2026 the front and rear wings will be ‘opened' whenever a car is in a part of the track designated by the FIA as not being traction limited – and we got a first taste of that in Abu Dhabi.

Permission was given to teams to develop a system that could open the upper-most element of the current front wings if they wanted, to use in this test.

It provides the teams, and Pirelli, with an initial estimate on the impact on drag levels and tyre load impacts to compare.

Mercedes ran a slightly crude design on Antonelli's mule car in the test with an actuation system on the upper elements of the front wing connected via large tubing to an internal system housed within the nosecone.

Ferrari had a much more refined version on display. It had already developed a system that was used in Pirelli's private mule car testing so it was unsurprisingly more subtle – the actuator on the front wing being connected by what looks like a carbon stem tucked neatly behind the wing and feeding back under the nosecone.

This created the novelty of seeing front wings being backed off on straights for the first time. But the systems are basic and the real thing in 2026 will be quite different.

Wheels look different in several ways

Pirelli unveiled a new look for its 2026 tyres at this test, with a change to the branding on the sidewall – which a surprising number of fans quickly noticed!

They'll look different in a couple of other ways next year too. First, as Pirelli boss Mario Isola handily demonstrated, the narrower 2026 tyres are actually quite noticeably smaller when compared to the 2025 ones. That's partly to save weight but primarily to reduce drag.

The test was handy for teams to better understand the narrower tyres and particularly how the contact patch, the part of the tyre that is touching the track surface that varies constantly with load, behaves and other characteristics of the narrower tyres.

These are not simply a scaled-down version of the 2025 tyres, because the change in size has necessitated a complete redesign.

Another experimental element in the Abu Dhabi test related to wheel rims, which will result in the biggest visual change.

While the mule car running has largely been conducted on adapted versions by the standard rim supplier, next year teams have more freedom with the designs.

In Abu Dhabi teams were permitted to conduct a limited number of runs with a wheel rim similar to what they will use in 2026.

McLaren was initially believed the only team believed to bring its own wheel rims to this test – but then Williams appeared with exposed wheels, without the covers we've become accustomed to in the current rules era.

That's a weight-saving change we can get behind because they just immediately looked so much better than their predecessors.

Norris has to wait for #1

New world champion Lando Norris was back behind the wheel of his McLaren in the morning of the test but not with the #1 on his car that'd hoped to have.

He ran with the #4 as normal but did at least mark his new status with a special gold crash helmet and rocked up in some world champion merchandise too.

The reason Norris couldn't run the number he wanted immediately? Technically, the season is not over and Norris is not yet officially world champion or permitted to change number.

That status is only confirmed at the FIA's end-of-year prizegiving ceremony which takes place on Friday in Uzbekistan.

Entry lists and car numbers are still relevant for race control and the timing system at the test, so the rule requiring car numbers to be shown on the front of the car and sides of the engine cover still apply as they perform an actual function.

And at the moment the #1 still 'belongs' to Max Verstappen.

Red Bull's new drivers got started

Red Bull was one of the greatest users of the young driver test back when it was much more common for teams to actually evaluate drivers.

Now it feels more like a duty for drivers already well embedded in a team's programme, or a chance for a rookie to log good mileage fairly safely.

What Red Bull did this time was somewhere between the two, because its driver line-ups are already set, but it used the test to get two new drivers a good 2026 head start.

New Red Bull Racing driver Isack Hadjar was given the full day of work in its mule car, which the team said was "hugely valuable" in getting to know him better and "develop that relationship heading into next year".

His replacement at Racing Bulls, F1 rookie Arvid Lindblad, also logged his first official laps with the team he will race for next year as until today he had only tested in private or been in the Red Bull for FP1 outings.

Lindblad's day was cut short by a car issue but Racing Bulls felt he is "getting up to speed very well" and Lindblad described it as putting "the basic foundations in place".

Some drivers didn't bother

It was a very busy day of running with the teams completing 13,984 kilometres (8698 miles) between them.

Combined with the ‘young driver' portion of the test there were 25 drivers on track in total across the day, 15 of whom will actually be racing next year.

The five who didn't: Max Verstappen, George Russell, Fernando Alonso, Lance Stroll and Franco Colapinto.

Red Bull gave its mule car to Hadjar, so that made sense, plus Verstappen didn't seem super keen anyway. And Mercedes' first-year driver Antonelli had the day to himself - which also has some logic given he is building experience.

Why Alpine didn't give Franco Colapinto much-needed seat time is unclear but as the team said "we have our full focus on next year" it maybe just felt Pierre Gasly was a better reference.

The biggest oddity was Aston Martin, as neither of its regular drivers bothered to take part. It was the only team that was the case for, with its test and reserve driver Stoffel Vandoorne filling in instead.

So who was fastest?

We saved this until last because timings in the test itself are largely irrelevant.

It takes place in the daytime, run plans are all over the place, some cars are shared across the day and there is different track evolution compared to qualifying at the weekend.

But with all that said, there is still timing, and someone ultimately ends the last ever official test of this era of F1 car, and this era of engine, quickest.

Step forward: Jak Crawford, whose 1m23.766s was around 0.8s slower than the fastest Aston Martin time in qualifying for the grand prix.